Introduction

Sake, often referred to as Japanese rice wine, is a beverage with a rich tapestry of history and cultural significance. Unlike traditional wines made from grapes, it is brewed from rice, a staple crop that has been central to Japanese agriculture and cuisine for millennia. The origins of sake are shrouded in ancient rituals and folklore, making it not just a drink, but a symbol of Japanese heritage and tradition.

Imagine a serene temple in the Japanese countryside, where monks meticulously brew sake as an offering to the gods. Picture a lively festival where locals gather to celebrate the harvest, sharing cups of sake to mark the occasion. These scenes highlight the integral role that sake has played in Japanese society, from religious ceremonies and royal courts to the bustling izakayas of modern cities.

This comprehensive guide will take you on a journey through the fascinating world of sake. We will explore its ancient origins and the evolution of its brewing techniques, delving into the meticulous process that transforms rice and water into this exquisite beverage. You will learn about the various types, each with its own unique characteristics and flavors, and discover the art of sake tasting and pairing. Finally, we will look at sake’s place in contemporary culture, both in Japan and around the world, highlighting its growing popularity and influence.

Whether you are a seasoned sake enthusiast or a curious newcomer, this guide aims to deepen your appreciation for this remarkable drink. Join us as we uncover the secrets of sake, a true embodiment of Japanese craftsmanship and tradition.

I. The History of Sake

A. Origins and Early History

Sake’s origins can be traced back over 2,000 years to ancient Japan, where rice cultivation first began. Early sake production likely started as a simple fermentation process where rice was chewed and then spit into a communal tub, allowing natural enzymes from saliva to break down the starches into sugars. This primitive method, known as “kuchikami no sake” or “mouth-chewed sake,” eventually gave way to more sophisticated brewing techniques.

As rice agriculture flourished, so did the methods of sake production. By the Nara period (710-794 AD), sake brewing had become more refined, with the use of koji mold to aid in the fermentation process. This period also saw the establishment of the first sake breweries, often associated with Shinto shrines and temples, where sake was brewed for religious ceremonies and offerings to the gods.

B. Sake in Japanese Culture

Sake has always been more than just a beverage in Japan; it is deeply embedded in the cultural and spiritual fabric of the country. In Shinto rituals, sake is considered a sacred offering to the gods, known as “omiki.” Ceremonial uses of sake include weddings, where it is consumed during the “san-san-kudo” ritual to symbolize unity and mutual respect between the bride and groom.

Throughout Japanese history, sake has played a role in social and political events. During the Heian period (794-1185 AD), sake was enjoyed by the imperial court and nobility, often accompanied by elaborate poetry and music. Festivals and seasonal celebrations also featured sake prominently, with each region developing its own unique customs and traditions around its consumption.

C. Modern Developments

The Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century brought significant changes to sake production. Industrialization introduced modern brewing equipment and techniques, allowing for greater consistency and quality control. The establishment of the National Research Institute of Brewing in 1904 further advanced the science of sake brewing, leading to innovations such as pasteurization and improved fermentation methods.

In the 20th century, sake faced challenges from the rise of beer and other alcoholic beverages, but it has experienced a resurgence in recent years. The craft sake movement has sparked renewed interest in traditional brewing techniques, with many small breweries focusing on artisanal production methods. This revival has also seen the emergence of new sake styles and flavors, appealing to a broader audience both in Japan and internationally.

Today, sake continues to evolve, blending time-honored traditions with modern innovations. It remains an integral part of Japanese culture, celebrated for its rich history, diverse varieties, and the craftsmanship involved in its production. As sake gains popularity worldwide, it serves as a bridge, connecting people to the ancient customs and contemporary spirit of Japan.

II. The Production Process

A. Ingredients

The production of sake relies on a few key ingredients, each contributing to the final product’s flavor and quality.

- Rice: The cornerstone of sake brewing is rice, but not just any rice. Sake rice, known as “sakamai,” is specifically cultivated for brewing purposes. It has larger grains with a higher starch content and fewer proteins and fats, which can affect flavor. Notable varieties of sake rice include Yamada Nishiki, Omachi, and Gohyakumangoku.

- Water: Water is crucial in sake production, making up about 80% of the final product. The mineral content of the water, particularly its levels of iron and manganese, can significantly influence the taste. Famous sake-brewing regions in Japan, such as Fushimi and Nada, are known for their high-quality water sources.

- Koji Mold: Koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) is essential for converting rice starches into fermentable sugars. This process, known as saccharification, is fundamental to brewing sake. Koji mold is cultivated on steamed rice to produce “koji rice.”

- Yeast: Yeast ferments the sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Different yeast strains can impart various aromas and flavors to the sake. The Brewing Society of Japan has developed specific yeast strains, such as Kyokai No. 7 and Kyokai No. 9, which are commonly used in sake production.

B. Brewing Techniques

The brewing process of sake is intricate and involves several stages, each requiring meticulous care and attention.

- Washing and Soaking: The sake rice is thoroughly washed to remove any impurities and then soaked in water to achieve the desired moisture content. The soaking time is carefully controlled based on the type of sake being produced.

- Steaming: The soaked rice is steamed to soften the grains, making them suitable for koji mold cultivation and fermentation. Steaming also sterilizes the rice, ensuring a clean fermentation process.

- Koji Making: Steamed rice is inoculated with koji mold and kept in a warm, humid environment to promote mold growth. This process, taking about 48 hours, results in koji rice, which is crucial for saccharification.

- Fermentation: Fermentation occurs in multiple stages. Initially, a small starter batch called “shubo” or “moto” is prepared, where koji rice, steamed rice, water, and yeast are mixed. This starter is then transferred to a larger tank, where more steamed rice, koji rice, and water are added in three successive stages over several days. This process, known as “sandanjikomi,” gradually builds up the fermentation mash.

- Pressing: After fermentation, the sake mash, now called “moromi,” is pressed to separate the liquid from the solid rice particles. Traditional methods use a cloth bag press called “fune,” while modern methods may use hydraulic presses.

- Pasteurization: Most sake undergoes pasteurization to stabilize it and prevent unwanted fermentation. This process involves heating the sake to about 60°C (140°F) for a short period. Some sakes, known as “namazake,” are not pasteurized and must be kept refrigerated.

- Aging: Sake is typically aged for a few months to a year to develop its flavor profile. The aging period and conditions, such as temperature and storage vessel, can influence the final taste.

- Bottling: After aging, the sake is filtered and diluted with water to achieve the desired alcohol content, usually around 15-20%. It is then bottled and sometimes pasteurized again before being distributed.

C. Aging and Bottling

The aging and bottling process is the final step in sake production and plays a crucial role in defining the sake’s character.

- Aging Techniques: Sake can be aged in various ways, including tank aging, where it is stored in large tanks, or bottle aging, where it is aged in bottles. The aging period can range from a few months to several years, with some specialty sakes aged for decades. Aged sake, known as “koshu,” develops complex flavors and aromas, often resembling sherry or brandy.

- Bottling: Once the sake has aged to the desired level, it is carefully filtered to remove any remaining solids. The sake is then diluted with water to achieve the desired alcohol content, usually around 15-20%. It may undergo a final pasteurization to ensure stability and prevent spoilage. The sake is then bottled and sealed, ready for distribution and consumption.

The meticulous production process, from selecting high-quality ingredients to precise brewing techniques, results in the diverse and nuanced flavors that sake enthusiasts around the world appreciate. Each step, whether steeped in tradition or enhanced by modern innovation, contributes to the unique character of sake, making it a truly remarkable beverage.

III. Types of Sake

A. Junmai and Honjozo

Junmai and Honjozo are two foundational types of sake, each offering distinct characteristics based on their ingredients and brewing processes.

- Junmai (純米酒):

- Ingredients: Pure rice sake, made only with rice, water, koji mold, and yeast, without any added alcohol.

- Characteristics: Rich, full-bodied flavors with a pronounced rice taste. Junmai sake tends to have a higher acidity and umami content, making it a versatile pairing with a variety of foods.

- Serving Suggestions: Can be enjoyed both warm and chilled, depending on the specific sake and personal preference.

- Honjozo (本醸造):

- Ingredients: Made with rice, water, koji mold, yeast, and a small amount of distilled alcohol added to enhance flavor and aroma.

- Characteristics: Lighter and more fragrant than Junmai sake, with a smoother, more refined taste. The added alcohol helps to extract additional flavors during brewing.

- Serving Suggestions: Typically enjoyed slightly chilled or at room temperature, highlighting its delicate balance.

B. Ginjo and Daiginjo

Ginjo and Daiginjo are premium types of sake, distinguished by the degree of rice polishing, which significantly affects their flavor profiles.

- Ginjo (吟醸酒):

- Rice Polishing Ratio: At least 40% of the rice grain is polished away, leaving no more than 60% of the original grain.

- Characteristics: Elegant, fragrant, and complex flavors with fruity and floral notes. Ginjo sake is brewed at lower temperatures, requiring more meticulous care.

- Serving Suggestions: Best enjoyed chilled to appreciate its delicate aromas and nuanced flavors.

- Daiginjo (大吟醸酒):

- Rice Polishing Ratio: At least 50% of the rice grain is polished away, leaving no more than 50% of the original grain.

- Characteristics: Extremely refined and sophisticated, with a lighter, more aromatic profile compared to Ginjo. Daiginjo sake is often considered the pinnacle of sake craftsmanship.

- Serving Suggestions: Always served chilled to preserve its intricate and delicate characteristics.

C. Nigori and Namazake

Nigori and Namazake are distinctive types of sake that offer unique textures and flavors.

- Nigori (濁り酒):

- Characteristics: Unfiltered or coarsely filtered sake that retains rice particles, giving it a cloudy appearance. Nigori sake is often sweeter and creamier, with a rich, bold flavor.

- Serving Suggestions: Usually served chilled and shaken before pouring to evenly distribute the sediment. It pairs well with spicy foods and desserts.

- Namazake (生酒):

- Characteristics: Unpasteurized sake that retains a fresh, vibrant taste with lively, bright flavors. Namazake requires refrigeration to maintain its quality and prevent spoilage.

- Serving Suggestions: Always served chilled. Its fresh and zesty profile makes it a great match for light dishes such as sashimi and salads.

D. Other Varieties

Beyond the primary categories, there are several specialty sakes that offer unique and diverse tasting experiences.

- Sparkling Sake:

- Characteristics: Carbonated sake with a refreshing, effervescent quality. It can range from dry to sweet and is often lower in alcohol content.

- Serving Suggestions: Best enjoyed chilled, often as an aperitif or with light appetizers.

- Koshu (古酒):

- Characteristics: Aged sake, typically matured for several years, resulting in deep, complex flavors that can include notes of dried fruit, nuts, and spices. Koshu has a richer, more robust profile.

- Serving Suggestions: Served at room temperature or slightly warmed, and pairs well with rich, savory dishes.

- Taru Sake (樽酒):

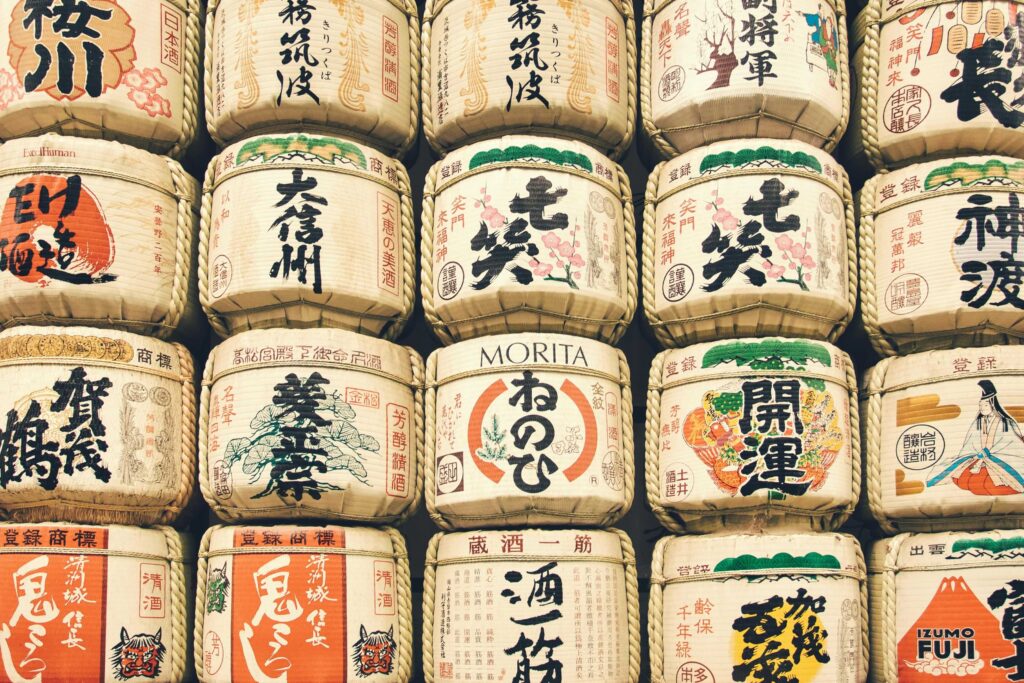

- Characteristics: Sake aged in cedar barrels, imparting a distinctive woody aroma and flavor. This traditional method gives Taru sake a unique character that is often associated with festive occasions.

- Serving Suggestions: Traditionally served in cedar cups to enhance its aromatic qualities. It pairs well with grilled foods and strong-flavored dishes.

- Regional Varieties:

- Each region in Japan produces sake with unique characteristics influenced by local ingredients, water sources, and brewing traditions. Notable regions include Niigata, known for its clean and dry sake, and Hiroshima, famous for its soft and mellow sakes.

These diverse types of sake showcase the depth and versatility of this traditional Japanese beverage, offering something for every palate and occasion. Whether you prefer the rich and robust flavors of Junmai or the elegant and refined notes of Daiginjo, there’s a sake to suit your taste.

IV. Sake Tasting and Pairing

A. The Art of Sake Tasting

Tasting sake is a nuanced and sensory experience that involves much more than simply drinking it. To fully appreciate the complexities of sake, follow these steps:

- Visual Examination:

- Observe the sake’s color and clarity. Most sakes are clear, but some may have a slight golden hue, indicating age or specific brewing methods. Cloudy sakes, like Nigori, will have a milky appearance.

- Aromas (Nose):

- Gently swirl the sake in the glass to release its aromas. Take a moment to inhale deeply. Note the bouquet, which may include fruity, floral, earthy, or even nutty scents. Each type of sake offers a unique aromatic profile.

- Tasting (Palate):

- Take a small sip and let it rest on your tongue. Pay attention to the initial taste, mid-palate, and finish. Note the flavors and textures—whether they are sweet, dry, rich, or light. Consider the balance of acidity, sweetness, and umami.

- Aftertaste:

- Evaluate the aftertaste, or “finish,” which is the lingering flavor left after swallowing. A good sake will have a pleasant and lasting finish.

B. Pairing Sake with Food

Sake’s versatility makes it an excellent companion to a wide range of foods. Here are some general principles and specific pairings:

- General Principles:

- Balance and Contrast: Match the sake’s flavor intensity with the dish. A delicate sake pairs well with light dishes, while a rich sake can complement heavier, more robust flavors.

- Complementing Flavors: Choose sakes that enhance the flavors of the food. For example, a sake with fruity notes can enhance a dish with similar fruity elements.

- Specific Pairings:

- Sushi and Sashimi: Pair with a light, crisp sake like Ginjo or Daiginjo to complement the delicate flavors of raw fish.

- Tempura: A medium-bodied sake like Honjozo balances the crispiness and subtle flavors of tempura.

- Grilled Meats: Rich, full-bodied sakes like Junmai or aged Koshu pair well with grilled meats, bringing out the umami flavors.

- Cheese: Surprisingly, sake pairs beautifully with cheese. Try a creamy Nigori with blue cheese or a sharp cheddar with a smooth, slightly sweet Junmai.

- Desserts: Sparkling sake or a sweet Nigori can be a delightful match for desserts, particularly those with fruit or creamy elements.

C. Sake Serving Etiquette

Understanding and respecting sake serving etiquette enhances the drinking experience and honors the cultural traditions associated with sake.

- Serving Practices:

- Pouring for Others: In Japanese culture, it is customary to pour sake for others rather than oneself. Hold the sake bottle with both hands and pour for your companions. They will reciprocate by pouring for you.

- Receiving Sake: When receiving sake, hold your cup with both hands as a sign of respect.

- Types of Sake Cups:

- Ochoko: Small, cylindrical cups traditionally used for sipping sake. They are often used during casual or formal occasions.

- Masu: Square wooden boxes originally used for measuring rice. Drinking sake from a masu adds a unique woody aroma to the experience.

- Tokkuri: A ceramic flask used to serve sake. The sake is poured from the tokkuri into individual cups.

- Wine Glasses: Increasingly, wine glasses are used to serve premium sakes like Ginjo and Daiginjo, as they help to concentrate and appreciate the delicate aromas.

- Temperature:

- Chilled (Reishu): Enhances the aromas and clean flavors, especially for Ginjo and Daiginjo sakes.

- Room Temperature (Jouon): Suitable for most sakes, allowing the full range of flavors to be appreciated.

- Warm (Nurukan): Often used for Junmai and Honjozo sakes. Heating sake can mellow out flavors and enhance richness.

- Hot (Atsukan): Occasionally used for less premium sakes to enhance warmth and comfort, particularly in colder weather.

Exploring the art of sake tasting and pairing can open up a world of flavors and experiences. By understanding how to taste sake, pair it with different foods, and serve it properly, you can deepen your appreciation for this ancient and versatile beverage.

V. Sake in Modern Culture

A. Sake Breweries and Tourism

- Famous Sake Regions:

- Niigata: Known for its pristine water and premium rice, Niigata produces some of Japan’s most elegant and dry sakes.

- Kyoto (Fushimi): Famed for its soft water, Fushimi sake is typically light and smooth, making it a favorite among many.

- Hyogo (Nada): One of Japan’s most productive sake regions, known for its robust and full-bodied sakes, often made with Yamada Nishiki rice.

- Hiroshima: Known for its innovative brewing techniques and mellow, slightly sweet sakes.

- Brewery Tours:

- Many sake breweries offer tours, providing an opportunity to see the production process firsthand, from rice polishing to fermentation and bottling.

- Tours often include tastings, allowing visitors to sample a variety of sakes and learn about the nuances of different types.

- Sake Tasting Experiences:

- Local Festivals: Sake festivals are held throughout Japan, featuring tastings, food pairings, and cultural performances.

- Sake Bars (Izayaka): These establishments offer extensive sake menus and knowledgeable staff who can guide guests through tasting experiences.

B. Sake in the Global Market

- Growing Popularity:

- Sake has seen a surge in popularity outside Japan, with increasing demand in North America, Europe, and other regions.

- The versatility and unique flavors of sake have captured the interest of sommeliers, chefs, and consumers worldwide.

- International Sake Producers:

- Countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia have started producing their own sakes, often incorporating local ingredients and techniques.

- International sake competitions, such as the International Wine Challenge Sake Competition, have helped to raise global awareness and appreciation for sake.

- Export Trends:

- Japanese sake exports have been rising steadily, driven by the growing global interest.

- Major export markets include the United States, China, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

C. Sake and Pop Culture

- Movies and Anime:

- Sake frequently appears in Japanese films and anime, often symbolizing tradition, celebration, or personal moments of reflection.

- Notable examples include Studio Ghibli films, where sake is depicted in scenes of community and connection.

- Contemporary Dining Trends:

- The rise of Japanese cuisine worldwide has brought sake to the forefront, often featured prominently in sushi restaurants and fine dining establishments.

- Sake pairings are increasingly popular, with chefs creating menus that highlight the complementary flavors of food and sake.

- Cultural Influence:

- Sake has become a symbol of Japanese culture and hospitality, often presented as a gift to mark special occasions or as a gesture of goodwill.

- Sake-themed merchandise, such as sake sets and accessories, has also gained popularity, reflecting the beverage’s cultural significance.

- Social Media and Sake Influencers:

- Social media platforms have played a significant role in spreading sake culture, with influencers and sake enthusiasts sharing their experiences, reviews, and recommendations.

- Online communities and forums provide a space for sake lovers to discuss and explore different types of sake, brewing techniques, and food pairings.

Conclusion

Sake, with its rich history and intricate production process, stands as a testament to Japanese craftsmanship and cultural heritage. From its ancient origins as a sacred ritual offering to its modern resurgence as a globally appreciated beverage, sake embodies the essence of tradition and innovation. The meticulous brewing techniques, the diverse types of sake, and the art of tasting and pairing all contribute to its unique appeal.

As we have explored in this guide, sake is not just a drink but a cultural experience. Each sip tells a story of the land, the water, the rice, and the people who dedicate their lives to perfecting this craft. Whether enjoyed in a traditional setting or a contemporary dining environment, sake brings people together, fostering a sense of community and connection.

The growing interest in sake around the world highlights its versatility and universal appeal. Sake breweries and tasting experiences offer a glimpse into the artistry and dedication behind each bottle. The increasing presence of sake in the global market and its influence in pop culture further underscore its enduring relevance.

As you embark on your own journey of sake discovery, remember to savor each moment and appreciate the depth of flavors and history in every glass. Whether you are a seasoned connoisseur or a curious newcomer, there is always something new to learn and enjoy about sake.

So, raise your glass and toast to the world of sake—a timeless tradition that continues to evolve and inspire. Kanpai!

Additional Resources

- Glossary of Terms: Definitions of key sake-related terms to enhance your understanding and appreciation.

- Recommended Reading and Websites: Books, articles, and websites for further exploration into the world of sake.

- Sake Tasting Events and Festivals: Information on where to experience sake tastings and cultural festivals, both in Japan and internationally.

By diving deeper into the world of sake, you can enrich your knowledge and enjoy the diverse and intricate flavors that this remarkable beverage has to offer. Explore, taste, and celebrate the art of sake, and let it bring a touch of Japanese culture into your life.