Introduction

The Boshin War (1868–1869) was a pivotal conflict that dramatically reshaped the course of Japanese history, signaling the end of the feudal era and the dawn of the Meiji Restoration. Fought between forces loyal to the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate and those seeking to return political power to the Emperor, the war was not only a struggle for military dominance but also a battle over Japan’s future direction. While the clash lasted only a little over a year, its consequences were far-reaching, catalyzing a series of political, social, and economic changes that laid the foundation for modern Japan.

In the mid-19th century, Japan was experiencing internal turmoil, sparked by the arrival of Western powers and the subsequent signing of unequal treaties that undermined the country’s sovereignty. Discontent brewed among various domains, especially in regions like Satsuma and Chōshū, who viewed the Tokugawa’s inability to repel foreign influence as a failure of leadership. The slogan Sonnō Jōi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) gained traction, symbolizing a growing desire to restore Imperial rule and expel foreign presence. Against this backdrop, the Boshin War erupted, forever changing the nation’s trajectory.

This blog post will explore the origins, key battles, and significant figures of the Boshin War, while highlighting how this seemingly brief conflict ushered in an era of unprecedented modernization and reform. By examining the events and aftermath of the Boshin War, we can better understand how Japan’s transition from a feudal shogunate to a centralized, modern state was not merely a top-down process but one forged through intense conflict and dramatic social transformation.

Political Landscape of the Late Edo Period

The political landscape of Japan in the late Edo Period was marked by growing instability and dissatisfaction with the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate, which had governed Japan for over 250 years. While the country had enjoyed a long period of relative peace under the Tokugawa’s centralized feudal system, the arrival of foreign powers and internal discontent exposed cracks in the shogunate’s authority and ultimately led to its downfall.

The Decline of the Tokugawa Bakufu

By the mid-19th century, the Tokugawa Bakufu was struggling to maintain its grip on power. Corruption within the administration, financial mismanagement, and an increasingly rigid class structure contributed to widespread disillusionment among the populace. The shogunate’s inability to adapt to changing economic conditions led to the decline of its financial power, while the samurai class, traditionally the backbone of the regime, faced economic hardships and loss of status. As the Bakufu failed to effectively address these issues, discontent simmered among various factions, including the samurai and local daimyo (feudal lords).

Foreign Pressure and the Unequal Treaties

The real catalyst for the shogunate’s crisis, however, came from the outside. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy arrived in Japan, demanding the opening of ports for trade and the establishment of diplomatic relations. Faced with superior Western technology and military power, the Tokugawa reluctantly signed the Treaty of Kanagawa in 1854, ending over 200 years of Japan’s self-imposed isolation. This was followed by a series of similar treaties with other Western nations, which granted extraterritorial rights and tariff concessions, making Japan a semi-colonial state in the eyes of many Japanese.

The shogunate’s acquiescence to foreign demands fueled resentment among the ruling class and the public, who saw this as a humiliating capitulation that undermined Japan’s sovereignty. As a result, opposition to the Tokugawa grew stronger, with domains like Satsuma and Chōshū leading the charge for change. These domains, which had retained a significant degree of autonomy and military power, began to form alliances and advocate for the overthrow of the Bakufu.

The Rise of the Sonnō Jōi Movement

At the heart of the opposition movement was the ideology of Sonnō Jōi (尊王攘夷), which translates to “Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians.” This slogan captured the essence of the anti-Bakufu sentiment, advocating for the restoration of the Emperor as the true ruler of Japan and the expulsion of all foreign influences. The movement gained support from samurai, intellectuals, and even commoners, who saw the Emperor as a symbol of unity and national strength.

Satsuma and Chōshū, the two most powerful domains in western Japan, became the leading proponents of Sonnō Jōi. Despite initially advocating for isolation and anti-foreign policies, they soon realized that defeating the Bakufu would require adopting Western technology and military strategies. As a result, they began modernizing their forces, acquiring Western-style firearms and ships, and training their troops in Western tactics. This pragmatic approach would later prove decisive in their eventual victory over the Tokugawa.

The Road to War: Key Events Leading Up to Conflict

The Boshin War was the culmination of years of political tension, strategic alliances, and pivotal events that set the stage for an armed confrontation between the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Imperial forces. While the conflict itself lasted just over a year, its roots stretched back to the mid-19th century, when a series of domestic and international developments began to erode the shogunate’s power. This section delves into the crucial moments and decisions that ultimately led to the outbreak of war.

The Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance (1866)

One of the most significant turning points leading up to the Boshin War was the formation of the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance in 1866. Historically rivals, the Satsuma and Chōshū domains set aside their differences and united against their common enemy: the Tokugawa Shogunate. The alliance was brokered by Saigō Takamori of Satsuma and Kido Takayoshi of Chōshū, two of the most influential figures in Japan’s pro-Imperial faction. The agreement established a military and political partnership between the two domains, combining their resources, influence, and military strength.

The Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance was not only a marriage of convenience but also a strategic maneuver that altered the balance of power in Japan. While Chōshū had already openly defied the shogunate by supporting the Imperial cause, Satsuma had maintained a more cautious stance. However, the shogunate’s aggressive policies and failed attempts to subdue Chōshū militarily pushed Satsuma to abandon its neutrality. The alliance effectively created a formidable force capable of challenging the Tokugawa’s authority, and it laid the groundwork for the eventual campaign against the shogunate.

The Death of Emperor Kōmei and the Ascension of Emperor Meiji (1867)

The sudden death of Emperor Kōmei in January 1867 marked a critical juncture in Japan’s political landscape. Emperor Kōmei had been a staunch supporter of Sonnō Jōi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) and had often voiced his disapproval of the shogunate’s conciliatory stance toward foreign powers. His death created a power vacuum that the pro-Imperial forces were quick to exploit.

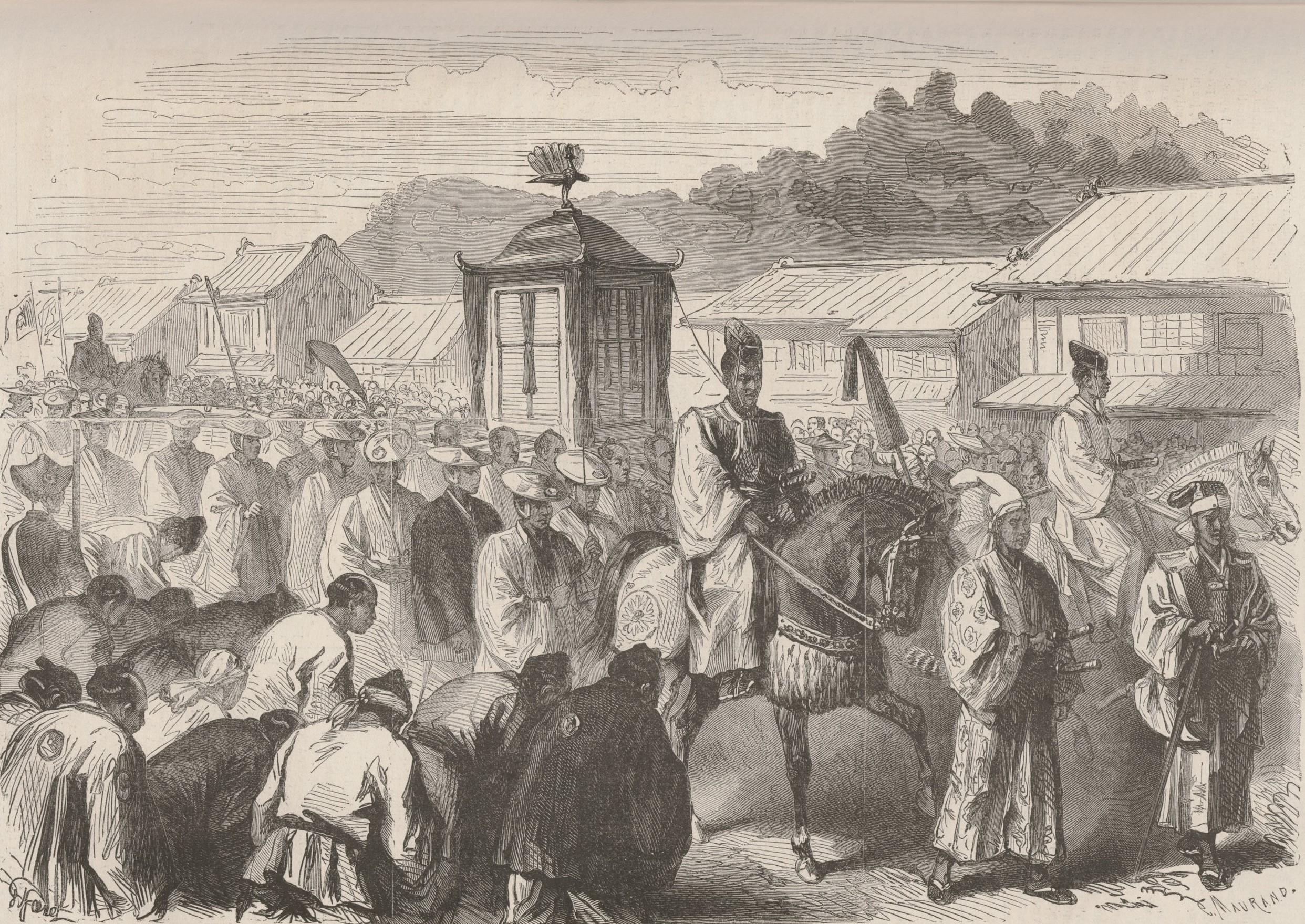

The ascension of the young Emperor Meiji, only 15 years old at the time, provided the anti-Tokugawa factions with a new symbol of hope and a rallying point for their cause. The Imperial Court, now more firmly under the influence of reform-minded leaders, began to assert its authority more forcefully. This shift emboldened the Satsuma and Chōshū domains, who viewed the young Emperor as a malleable figurehead through whom they could consolidate their power and achieve their goal of restoring Imperial rule.

The Return of Political Power to the Emperor (Taisei Hōkan, 1867)

Facing mounting pressure and recognizing the growing strength of the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th and final shogun, made a dramatic move. On November 9, 1867, Yoshinobu offered to resign his position as shogun and return political power to the Emperor in an event known as the Taisei Hōkan (大政奉還, “Return of the Governing Power”). Yoshinobu’s resignation was intended to facilitate a peaceful transition and allow the Tokugawa to retain significant influence in a new political structure.

However, this move did not have the desired effect. Instead of quelling the ambitions of the pro-Imperial forces, it spurred them to push for the complete dismantling of the Tokugawa regime. The resignation also sparked debates within the Imperial Court, where factions argued over how much power should be granted to Yoshinobu and the Tokugawa family in the new government. The situation remained precarious, with both sides unsure of how to proceed, setting the stage for further conflict.

The Decree to Strip the Tokugawa of Their Titles and Land (1868)

In January 1868, the pro-Imperial forces took a decisive step by issuing a decree that stripped Tokugawa Yoshinobu of his titles and lands. This decree was a direct challenge to the shogunate’s authority and a declaration that the Tokugawa no longer had a place in the new government. Angered by this decision, Yoshinobu resolved to take military action to defend the Tokugawa’s honor and legacy.

The decree effectively nullified the Taisei Hōkan agreement and left Yoshinobu with no other option but to mobilize his forces. Viewing the decree as an insult and a violation of the agreement, Yoshinobu ordered his troops to march on Kyoto, where the Imperial Court was based. This move was a desperate attempt to reassert the Tokugawa’s authority and bring the pro-Imperial forces to the negotiating table.

Outbreak of the Boshin War (1868)

The outbreak of the Boshin War in January 1868 marked the beginning of a conflict that would decisively end the Tokugawa Shogunate’s reign and set Japan on a path toward rapid modernization and centralization. What began as a localized skirmish near Kyoto soon escalated into a full-scale war that spread across the country, from the Kanto region to the far reaches of Hokkaido. The war saw the deployment of newly modernized armies, the use of Western military tactics, and a clash of ideologies that pitted the old feudal order against the forces of a new, unified Japan under the Emperor.

The Battle of Toba-Fushimi (January 27–30, 1868)

The Boshin War formally began with the Battle of Toba-Fushimi, a four-day engagement near Kyoto that set the tone for the entire conflict. Tokugawa Yoshinobu, determined to reassert his authority after being stripped of his titles and lands by the Imperial Court, ordered his forces to march on Kyoto in an attempt to seize control of the city and pressure the Emperor’s supporters into backing down.

The Tokugawa army, numbering approximately 15,000 troops, faced off against a much smaller but highly motivated force of about 5,000 soldiers from the Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa domains, who were fighting under the banner of the newly-formed Imperial Army. The battle was significant not only for its military outcome but also for its symbolic importance. The pro-Imperial forces hoisted the Emperor’s standard—a powerful psychological tool that demoralized many Tokugawa troops, who hesitated to fight against what they perceived as the Emperor’s will.

Despite their numerical advantage, the Tokugawa forces were outmaneuvered and decisively defeated. A key factor in their loss was the superior weaponry and tactics of the Imperial Army, which had adopted Western-style firearms, artillery, and battlefield strategies. Many Tokugawa soldiers, equipped with outdated matchlock guns and spears, were unprepared for the modern warfare tactics employed by their opponents. After sustaining heavy losses, Tokugawa Yoshinobu ordered a retreat to Osaka Castle and then fled by ship to Edo, abandoning his troops and leaving them in disarray.

The Fall of Osaka Castle and Yoshinobu’s Flight to Edo

The defeat at Toba-Fushimi was a devastating blow to Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s authority and morale. Realizing that his position was untenable, Yoshinobu made the controversial decision to flee from Osaka Castle to Edo by ship, effectively abandoning his remaining forces. This move was seen as an act of cowardice by many of his retainers and further eroded support for the shogunate.

The fall of Osaka Castle in February 1868 to the advancing Imperial forces marked the symbolic end of Tokugawa dominance in the Kansai region. With Osaka, the Tokugawa’s western stronghold, now under Imperial control, the path was clear for a march toward Edo, the Tokugawa capital. The Imperial forces continued their advance, and by March 1868, they had reached the outskirts of Edo.

The Bloodless Surrender of Edo Castle (May 3, 1868)

With Imperial troops at the gates of Edo, one of the world’s largest cities at the time, a full-scale battle would have resulted in massive casualties and widespread destruction. Instead, a historic meeting took place between Saigō Takamori, representing the Imperial Army, and Katsu Kaishū, a senior Tokugawa official known for his diplomatic skills. Katsu convinced Saigō to spare Edo from the ravages of war, and the two men negotiated a peaceful surrender of the city.

On May 3, 1868, Edo Castle was handed over to the Imperial forces without a single shot being fired. This “bloodless surrender” was a crucial turning point in the Boshin War, allowing the Imperial forces to take control of the shogunate’s capital with minimal resistance. The peaceful transfer of Edo demonstrated that, while the conflict was primarily military, there were still those on both sides who prioritized the stability and future of the nation over immediate victory.

The Expansion of the Conflict to Northern Honshu

Despite the peaceful surrender of Edo, many Tokugawa loyalists, particularly in the northeastern domains of northern Honshu, refused to submit. These domains, led by the Sendai and Aizu domains, banded together to form the Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei (Northern Alliance), a coalition of domains that pledged to continue the fight against the Imperial forces.

The Northern Alliance, however, faced significant challenges. The coalition was hampered by a lack of coordination, regional rivalries, and the superior resources of the Imperial Army. After a series of battles throughout northern Honshu, the Imperial forces captured the strategically vital Aizu domain in November 1868, effectively breaking the power of the Northern Alliance. The fall of Aizu marked the end of organized resistance in Honshu and shifted the focus of the war to the final Tokugawa stronghold: the island of Hokkaido.

The Establishment of the Ezo Republic in Hokkaido

Following their defeat in Honshu, a group of Tokugawa loyalists, led by Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, fled to the northern island of Hokkaido. There, they established the Ezo Republic, with Enomoto as its president. The Ezo Republic, however, was more of a temporary holdout than a legitimate government. While it adopted elements of Western-style governance and sought international recognition, it lacked the military strength and support to sustain itself against the Imperial forces.

The Imperial Army, now bolstered by its victories in Honshu, launched an assault on Hokkaido in the spring of 1869. After several months of fighting, the Imperial forces defeated the Tokugawa loyalists at the Battle of Hakodate, bringing an end to the Ezo Republic. Enomoto Takeaki surrendered in June 1869, signaling the end of the Boshin War.

Key Battles and Turning Points

The Boshin War was marked by several key battles and turning points that shifted the momentum of the conflict and ultimately determined its outcome. While some engagements were decisive military victories, others had a profound psychological and symbolic impact on the combatants and observers alike. This section examines the most significant battles and turning points that shaped the course of the Boshin War and led to the eventual downfall of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

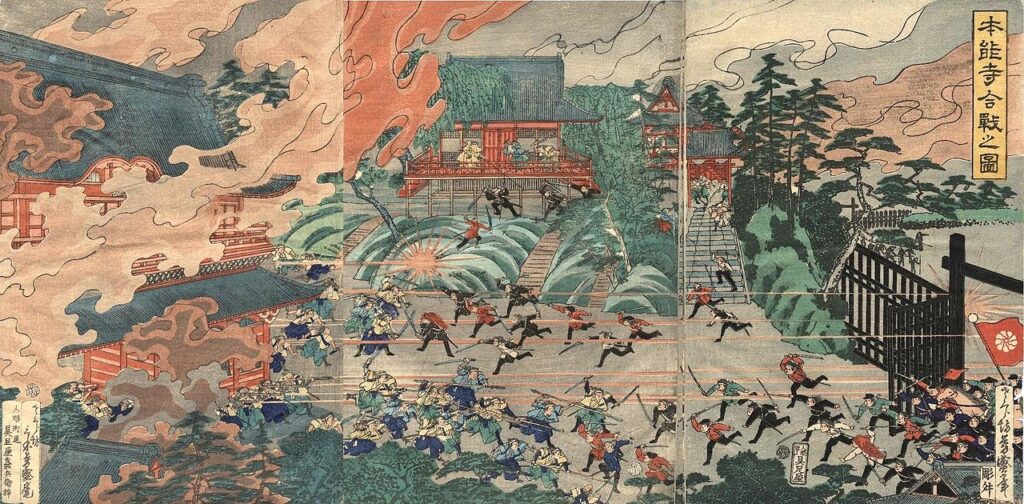

The Battle of Toba-Fushimi (January 27–30, 1868)

The Battle of Toba-Fushimi was the first major engagement of the Boshin War and is widely regarded as the pivotal turning point in the conflict. The battle took place on the outskirts of Kyoto and pitted the Tokugawa forces, numbering around 15,000 troops, against a smaller Imperial army of approximately 5,000 soldiers from the Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa domains.

Despite their numerical superiority, the Tokugawa forces suffered a humiliating defeat. Several factors contributed to their loss, including outdated weaponry, lack of coordination, and the psychological effect of seeing their opponents fight under the Emperor’s banner. The use of modern Western-style firearms and artillery by the Imperial forces also played a decisive role. The pro-Imperial troops’ superior training and adoption of modern tactics allowed them to outmaneuver and overpower the Tokugawa soldiers.

The defeat at Toba-Fushimi shattered the morale of the Tokugawa forces and marked the beginning of the end for the shogunate. Tokugawa Yoshinobu, who had personally overseen the battle from Osaka Castle, fled to Edo in a state of despair, effectively abandoning his remaining forces. This withdrawal signaled to many that the shogunate’s authority was crumbling, encouraging more domains to side with the Imperial Court.

The Fall of Edo (May 3, 1868)

The fall of Edo, the Tokugawa capital, was another key turning point in the Boshin War. After their victory at Toba-Fushimi, the Imperial forces marched toward Edo, where Tokugawa Yoshinobu had retreated. Edo, one of the largest cities in the world at the time, was not only the political center of the shogunate but also a potential flashpoint for a devastating urban conflict.

Rather than launching an all-out assault, the Imperial forces, led by Saigō Takamori, opted for a diplomatic approach. Saigō entered into negotiations with Katsu Kaishū, a senior Tokugawa official who advocated for a peaceful resolution. Katsu successfully persuaded Saigō to avoid a bloody confrontation, arguing that sparing Edo would prevent unnecessary loss of life and help preserve the unity of the nation.

On May 3, 1868, Edo Castle was peacefully handed over to the Imperial forces in what became known as the “bloodless surrender.” The absence of a battle in Edo marked a significant psychological victory for the Imperial side, as it allowed them to take control of the Tokugawa capital with minimal resistance. This event solidified the Imperial Court’s position as the dominant power in Japan and undermined the resolve of remaining Tokugawa loyalists.

The Battle of Ueno (July 4, 1868)

The Battle of Ueno was one of the last major engagements in Edo and represented the final stand of the Shōgitai, an elite corps of Tokugawa retainers who refused to surrender. Stationed at Kan’ei-ji Temple in the Ueno district, the Shōgitai, numbering around 2,000 men, hoped to rally support for a counteroffensive against the Imperial forces.

However, their resistance proved futile. The Imperial forces, under the command of Ōmura Masujirō, attacked Ueno with overwhelming firepower, including modern artillery and rifles. The Shōgitai were outmatched and quickly overwhelmed. By the end of the day, the temple was in flames, and the remaining Tokugawa defenders were either killed, captured, or forced to flee. The Battle of Ueno effectively ended any hope of organized resistance in Edo and paved the way for the Imperial Army’s advance into northern Japan.

Naval Engagements: The Battles of Awa and Miyako Bay (1868)

Naval warfare played a crucial role in the Boshin War, as both sides sought to control Japan’s coastal regions and key shipping routes. Two important naval engagements—the Battle of Awa and the Battle of Miyako Bay—demonstrated the growing importance of Western-style warships and naval strategies in modern warfare.

- The Battle of Awa (January 28, 1868): Taking place on the same day as the Battle of Toba-Fushimi, the Battle of Awa was a naval skirmish between the Tokugawa fleet and the Imperial Navy near the Awa Province (present-day Chiba Prefecture). The Tokugawa fleet, though smaller, managed to inflict significant damage on the Imperial ships. However, the engagement had little strategic impact and ended with both sides withdrawing.

- The Battle of Miyako Bay (May 6, 1868): This engagement occurred as Tokugawa loyalists, led by Enomoto Takeaki, attempted to seize the Imperial warship Kōtetsu. The Kōtetsu, a modern ironclad warship, was the most advanced vessel in the Imperial fleet and symbolized the modernization efforts of the Meiji government. Enomoto’s plan failed, as the Imperial Navy repelled the assault and maintained control of the Kōtetsu. This victory was a major boost to the morale of the Imperial forces and secured their dominance at sea.

The Battle of Aizu (October–November 1868)

The Battle of Aizu was one of the largest and most protracted engagements of the Boshin War. The Aizu domain, located in northern Honshu, was a staunch Tokugawa stronghold and a major center of resistance against the Imperial forces. Led by Matsudaira Katamori, the Aizu samurai fought tenaciously to defend their territory.

Imperial forces, under the command of Ōmura Masujirō and others, besieged Aizu’s castle town of Wakamatsu for over a month. The defenders, including many women and children, held out valiantly, but the castle walls could not withstand the constant bombardment from modern artillery. On November 6, 1868, Wakamatsu Castle surrendered, marking the collapse of the Northern Alliance and the end of organized resistance in northern Honshu.

The fall of Aizu was a turning point that marked the effective end of the Boshin War in the main islands of Japan. With Aizu defeated, most of the remaining Tokugawa forces either surrendered or fled to Hokkaido, where they would make their final stand.

The Battle of Hakodate (May 1869)

The Battle of Hakodate was the final engagement of the Boshin War and took place on the northern island of Hokkaido. After the fall of Aizu, Tokugawa loyalists, led by Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, retreated to Hokkaido and established the Ezo Republic, the first and only attempt at a separate government outside the Imperial Court’s control.

The Imperial forces launched a full-scale invasion of Hokkaido in the spring of 1869. After a series of skirmishes, the decisive battle took place at the fortress of Goryōkaku, where the Tokugawa loyalists made their last stand. Despite their tenacity, the defenders were outnumbered and outgunned. Enomoto, recognizing the futility of further resistance, surrendered on June 27, 1869.

The fall of Hakodate and the dissolution of the Ezo Republic brought an end to the Boshin War, conclusively establishing the authority of the Meiji government over the entire country.

Impact of the Boshin War on Japan’s Transformation

The Boshin War was a transformative event in Japanese history, serving as the catalyst for the political, social, and economic changes that defined the Meiji Era (1868–1912). While the war itself lasted little more than a year, its consequences were far-reaching, setting the stage for the modernization and centralization of power under the Emperor. The aftermath of the conflict saw the dismantling of the feudal order, the restructuring of the military, and the rapid adoption of Western technologies and institutions. This section explores the profound impacts of the Boshin War on Japan’s transformation into a unified, modern state.

Dissolution of the Tokugawa Shogunate and Restoration of Imperial Authority

One of the most immediate and significant impacts of the Boshin War was the complete dissolution of the Tokugawa Shogunate. With the shogunate’s defeat, the era of samurai-dominated governance came to an end, and political power was restored to the Emperor for the first time in over 250 years. This “restoration” was more than a symbolic transfer of power; it marked the beginning of a new centralized government under Emperor Meiji, who became the focal point of Japan’s national identity and political authority.

The Meiji government, led by young and ambitious leaders from the Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa domains, began to establish a new political framework based on Western models of governance. The new regime abolished the traditional feudal system, replaced the fragmented power structures of the daimyo with a centralized bureaucratic state, and implemented policies aimed at modernizing the country. The Emperor, now officially recognized as the sovereign of Japan, served as a unifying figurehead for the new government, lending it legitimacy and fostering national cohesion.

Abolition of the Han System and the Centralization of Power

The abolition of the han system, which had defined Japan’s feudal political structure for centuries, was a crucial step in the country’s transformation. Under the han system, regional domains, governed by daimyo, operated with considerable autonomy, maintaining their own armies, economies, and policies. This decentralization had been a fundamental feature of Tokugawa rule, but it was also a major obstacle to the creation of a unified nation-state.

In 1871, just two years after the end of the Boshin War, the new Meiji government formally abolished the han system and replaced it with a prefectural system. Daimyo were compelled to surrender their lands and submit to the central government. In return, they were appointed as governors of newly established prefectures, but their role was largely symbolic, and they were soon replaced by officials loyal to the central authority. This reform effectively centralized power under the Meiji government, eliminating regional rivalries and enabling the implementation of nationwide policies that promoted modernization and industrialization.

Modernization of the Military and the Creation of a National Army

The Boshin War highlighted the need for a modern military capable of defending Japan against both internal threats and external powers. During the war, the Imperial forces had already begun to experiment with Western military organization and tactics, which contributed to their victory over the Tokugawa forces. After the war, the Meiji government embarked on a comprehensive restructuring of the military, drawing on Western models to create a modern, conscription-based army.

In 1873, the government introduced the Conscription Ordinance, which established universal military service for all males, regardless of social class. This policy was revolutionary in its aim to dissolve the traditional hierarchy that had defined the samurai class’s privileged status. The new Imperial Army was equipped with modern weapons, trained in Western tactics, and organized along European lines. The samurai, who had traditionally served as Japan’s warrior class, were gradually marginalized and eventually disbanded in favor of a professional national army that represented the new state’s centralized authority.

The modernization of the military not only strengthened Japan’s defense capabilities but also helped forge a sense of national identity and unity. The new army became a symbol of the Meiji government’s commitment to creating a powerful, modern state, capable of standing alongside the great powers of the world.

Social and Economic Reforms: The End of the Samurai Class

The Boshin War’s outcome also had profound social implications, particularly for the samurai class. The samurai, who had long been the ruling elite and warriors of Japan, found themselves increasingly irrelevant in the new Meiji state. The abolition of the han system and the establishment of a conscription-based military rendered the traditional role of the samurai obsolete.

The Meiji government introduced a series of reforms aimed at integrating the samurai into the broader society. These reforms included the end of stipends for samurai, the prohibition of carrying swords in public (symbolized by the Haitōrei Edict of 1876), and the encouragement of samurai to seek employment in the emerging sectors of government, industry, and education. While some samurai successfully adapted to these changes, many were left disenfranchised and disillusioned, leading to several uprisings, such as the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, which sought to restore the old order. These rebellions were crushed by the new Imperial Army, further cementing the government’s authority and the end of the samurai era.

Economic Modernization and Industrialization

The Meiji leaders recognized that economic strength was essential to ensuring Japan’s independence and prosperity. Inspired by Western industrialization, the government implemented policies that promoted the development of infrastructure, the establishment of modern industries, and the expansion of commerce.

The government embarked on a program of “Shokusan Kōgyō” (Encouragement of Industry), which involved state investment in shipbuilding, textile manufacturing, and mining. Railroads and telegraph lines were constructed to connect previously isolated regions, facilitating trade and communication. Western advisors were invited to Japan to help train Japanese workers and introduce new technologies, while Japanese students and officials were sent abroad to study Western systems firsthand.

These efforts laid the groundwork for Japan’s rapid industrialization, which accelerated in the latter half of the Meiji period. By the turn of the 20th century, Japan had emerged as a leading industrial power in Asia, capable of competing with Western nations both economically and militarily.

Educational and Institutional Reforms

In addition to political and economic reforms, the Meiji government placed a strong emphasis on education as a means to modernize and unify the nation. The introduction of a national education system, based on Western models, aimed to produce a literate and skilled population that could contribute to Japan’s modernization efforts.

The 1872 Education Order established a system of compulsory education, providing access to basic schooling for all children, regardless of social background. This focus on education helped create a new generation of Japanese citizens who were not only literate and well-versed in modern sciences but also instilled with a sense of loyalty to the Emperor and the state.

Westernization and Cultural Shifts

The Meiji government’s reforms extended beyond the political and economic spheres, touching nearly every aspect of Japanese society. Western ideas and customs began to permeate Japanese culture, leading to significant changes in clothing, architecture, and social practices. The adoption of Western dress, the construction of Western-style buildings, and the introduction of Western music and art forms all symbolized Japan’s desire to be seen as a modern, “civilized” nation.

However, this period of Westernization was also marked by efforts to preserve traditional Japanese culture. The government promoted a selective adoption of Western customs, carefully balancing modernization with the preservation of national identity. The result was a unique fusion of Eastern and Western elements that became a hallmark of the Meiji Era.

Notable Figures and Their Roles

The Boshin War was shaped by the actions and decisions of several key figures, each of whom played a crucial role in the conflict’s development and outcome. These leaders, both on the Imperial and Tokugawa sides, were instrumental not only in the battlefield strategies and political maneuvering of the war but also in shaping the course of Japan’s modernization and transformation during the Meiji Restoration. This section delves into the contributions, motivations, and legacies of some of the most notable figures involved in the Boshin War.

1. Saigō Takamori (1828–1877)

Saigō Takamori was one of the most prominent leaders of the pro-Imperial forces and is often remembered as a key architect of the Meiji Restoration. A samurai from the Satsuma domain, Saigō rose to prominence through his leadership in the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance, which played a pivotal role in overthrowing the Tokugawa Shogunate.

During the Boshin War, Saigō served as the commander of the Imperial forces and led them to a series of decisive victories, including the crucial Battle of Toba-Fushimi and the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle. His ability to negotiate the bloodless surrender of Edo demonstrated his skill as both a military leader and a diplomat. This action not only minimized the loss of life but also helped preserve the city’s infrastructure, facilitating a smoother transition to Imperial rule.

After the war, Saigō became a key figure in the new Meiji government. However, he grew increasingly disillusioned with the rapid pace of Westernization and the erosion of samurai traditions. His dissatisfaction culminated in the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, where he led a failed uprising against the government he had helped to establish. Saigō’s death at the end of the rebellion marked the final chapter in the samurai era. Despite his eventual opposition to the Meiji government, he is remembered as a tragic hero and symbol of loyalty and honor.

2. Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837–1913)

Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th and final shogun of the Tokugawa Shogunate, was a complex figure whose actions were central to the outbreak and resolution of the Boshin War. Known for his reformist mindset, Yoshinobu attempted to modernize the shogunate and strengthen its position in the face of mounting internal and external challenges. He introduced a number of reforms, such as modernizing the military and reorganizing the shogunate’s administrative structure.

However, Yoshinobu’s efforts came too late. Facing the united front of the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance and the growing influence of the pro-Imperial faction, he made the controversial decision to resign as shogun in 1867, returning political power to the Emperor in an attempt to preserve the Tokugawa family’s influence within a new government. His resignation, known as the Taisei Hōkan, was intended to be a peaceful transition of power, but it ultimately led to the outbreak of war as pro-Imperial forces sought to eliminate the Tokugawa’s influence entirely.

During the war, Yoshinobu remained largely passive, leaving military decisions to his subordinates. After his defeat at the Battle of Toba-Fushimi, he retreated to Edo and eventually negotiated the city’s peaceful surrender. Following the end of the Boshin War, Yoshinobu withdrew from public life and lived quietly, dedicating himself to hobbies such as photography and calligraphy. His legacy is that of a pragmatic but ultimately tragic figure, whose attempts to reform the shogunate and avoid conflict were overshadowed by the swift and decisive actions of his opponents.

3. Kido Takayoshi (1833–1877)

Kido Takayoshi, a samurai from the Chōshū domain, was a key strategist and political leader against the Tokugawa Shogunate. He was known for his political acumen and deep understanding of both domestic and international affairs. Kido played a crucial role in forming the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance, unifying the two most powerful anti-Tokugawa domains.

During the Boshin War, Kido served as a senior advisor to the Imperial Court. He secured support for the pro-Imperial cause from several key domains. He also advocated adopting Western military technologies and strategies, giving the Imperial forces a decisive edge over Tokugawa armies.

After the war, Kido became one of the principal architects of the Meiji government’s modernization policies. He championed educational reform, the establishment of a centralized administration, and the abolition of the feudal domain system. Despite his contributions, Kido struggled with health issues and political infighting within the Meiji government. He died in 1877, leaving behind a legacy as one of the driving forces behind Japan’s transformation into a modern state.

4. Ōkubo Toshimichi (1830–1878)

Ōkubo Toshimichi, another influential leader from the Satsuma domain, was a close ally of Saigō Takamori and Kido Takayoshi. As one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration, Ōkubo was a master tactician and statesman who played a pivotal role in both the political and military aspects of the Boshin War.

Ōkubo’s contributions were not limited to the battlefield. He was a key proponent of centralization and modernization, advocating for the dismantling of the feudal system and the creation of a strong, centralized state under the Emperor. His support for rapid Westernization made him a controversial figure, especially among more conservative elements within Japanese society.

After the Boshin War, Ōkubo became a powerful figure in the Meiji government, overseeing the implementation of major economic and social reforms. His policies helped lay the foundation for Japan’s industrialization and emergence as a global power. However, his support for the government’s anti-samurai policies and his role in suppressing the Satsuma Rebellion led to his assassination in 1878 by a group of disaffected samurai. Despite his untimely death, Ōkubo’s vision for a modern Japan continued to shape the country’s development for decades to come.

5. Enomoto Takeaki (1836–1908)

Enomoto Takeaki was a Tokugawa naval officer who became one of the most notable leaders of the shogunate’s forces during the Boshin War. Trained in the Netherlands, Enomoto was well-versed in Western naval tactics and technologies. As the Tokugawa Shogunate faced defeat on land, Enomoto sought to leverage the shogunate’s remaining naval power to establish a foothold in northern Japan.

After the fall of Edo, Enomoto led a fleet of Tokugawa loyalists to the northern island of Hokkaido, where they established the Ezo Republic, an autonomous government separate from the Imperial Court. Enomoto served as president of the Ezo Republic and attempted to create a Western-style government. However, the Imperial Army launched a campaign against the Ezo Republic, culminating in the Battle of Hakodate, where Enomoto’s forces were defeated.

Following his surrender, Enomoto was initially imprisoned but later pardoned by the Meiji government. Remarkably, he went on to serve the Meiji government in various high-ranking positions, including as a diplomat and cabinet minister. His post-war career demonstrated his adaptability and willingness to serve the new regime, making him one of the few Tokugawa loyalists to find success in the Meiji Era.

6. Matsudaira Katamori (1836–1893)

Matsudaira Katamori, the daimyo of the Aizu domain, was a staunch supporter of the Tokugawa Shogunate and one of its most loyal retainers. He served as the shogunate’s military commissioner in Kyoto and was instrumental in suppressing early pro-Imperial uprisings. His loyalty to the Tokugawa family made Aizu one of the main centers of resistance against the Imperial forces during the Boshin War.

The Aizu domain’s defense of Wakamatsu Castle was one of the most notable battles of the war, where Matsudaira and his samurai fought bravely against overwhelming odds. The fall of Aizu in 1868 marked the collapse of the Tokugawa resistance in northern Honshu. After the war, Matsudaira was stripped of his titles and lands, and he spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity. Despite his defeat, Matsudaira is remembered as a symbol of loyalty and honor, embodying the samurai spirit even in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Aftermath and Legacy

The aftermath of the Boshin War signified not only the end of centuries of samurai rule under the Tokugawa Shogunate but also the beginning of a transformative period in Japan’s history. The victory of the pro-Imperial forces led to the establishment of a new government that embraced modernization and a centralized state, setting the stage for the Meiji Restoration. The consequences of the war extended far beyond the battlefield, fundamentally altering Japan’s social, political, and economic landscapes. This section explores the immediate and long-term impacts of the Boshin War, as well as its enduring legacy in Japanese history.

The End of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Establishment of the Meiji Government

The most immediate consequence of the Boshin War was the dismantling of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which had ruled Japan for over 260 years. With the defeat of Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s forces and the eventual surrender of Edo Castle, the power of the shogunate was broken, and political authority was restored to Emperor Meiji. The restoration of the Emperor as the symbolic head of state marked the beginning of a new era—the Meiji Era (1868–1912).

The newly established Meiji government, dominated by young samurai leaders from the Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa domains, set about creating a centralized state. The Emperor, though now officially the supreme authority, was primarily a figurehead, while the real power rested with a small group of former samurai, known as the Meiji oligarchs. This new political structure enabled the rapid implementation of reforms and the consolidation of power under the central government, effectively ending the feudal system that had defined Japanese politics for centuries.

The Abolition of the Feudal System and Creation of a Modern State

One of the most significant changes implemented by the Meiji government was the abolition of the feudal domain (han) system in 1871. The traditional domains, governed by daimyo who enjoyed significant autonomy, were replaced with a new system of prefectures governed by officials appointed by the central government. This reform not only eliminated the power of the daimyo but also established a more unified and centralized administrative structure.

The abolition of the han system was part of a broader effort to create a modern nation-state capable of governing effectively and resisting external pressures. The new prefectural system laid the foundation for the development of a centralized bureaucracy, which facilitated the implementation of nationwide policies in areas such as education, industry, and taxation. By eliminating the power of the regional daimyo, the Meiji government ensured that all resources and authority were concentrated in the hands of the central government, enabling it to direct the country’s modernization efforts with greater efficiency.

The Demise of the Samurai Class and Social Reforms

The victory of the Imperial forces and the subsequent reforms had profound implications for the samurai class, which had traditionally served as Japan’s warrior elite. With the abolition of the han system, the samurai lost their stipends and social privileges, forcing them to seek new roles in the rapidly changing society. Many former samurai found employment in the new military or government, while others pursued careers in business, education, or agriculture. However, not all samurai were able to adapt to these changes, leading to social discontent and unrest.

The Meiji government’s decision to abolish the right of samurai to wear swords in public, symbolized by the Haitōrei Edict of 1876, further eroded the status and identity of the samurai class. This loss of privilege, combined with economic difficulties, led to several uprisings by disaffected samurai, the most notable being the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, led by Saigō Takamori. The suppression of the Satsuma Rebellion marked the final defeat of the samurai class and the consolidation of the new government’s power.

Rapid Modernization and Industrialization

The end of the Boshin War cleared the way for the Meiji government to embark on a comprehensive program of modernization and industrialization. Determined to avoid the fate of other Asian nations that had fallen under Western colonial rule, the Meiji leaders sought to build a strong, independent Japan capable of competing with the Western powers. This effort, known as the “Meiji Restoration,” was characterized by the adoption of Western technologies, institutions, and cultural practices.

The government introduced a series of reforms aimed at modernizing the economy, including the construction of railways, telegraph lines, and modern factories. State-sponsored enterprises, known as zaibatsu, were established to promote industrial growth in key sectors such as textiles, shipbuilding, and mining. The education system was also reformed to produce a skilled workforce capable of supporting the country’s modernization efforts. These changes laid the foundation for Japan’s rapid industrialization, transforming it from a largely agrarian society into a major industrial power within a few decades.

Formation of a Modern Military and National Identity

The Boshin War exposed the limitations of Japan’s traditional samurai-based military system and highlighted the need for a modern, conscription-based army. In 1873, the Meiji government introduced the Conscription Ordinance, which established universal military service for all males. This reform not only created a professional standing army but also helped foster a sense of national identity and loyalty to the Emperor.

The creation of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, modeled after the French and British military systems, respectively, strengthened Japan’s defense capabilities and enabled it to project power both domestically and abroad. By the end of the Meiji period, Japan had become the dominant military power in East Asia, as demonstrated by its victories in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).

The Emergence of Japan as a Global Power

The Boshin War and the subsequent Meiji Restoration set Japan on a path to becoming a global power. By the early 20th century, Japan had achieved a level of industrialization and military strength comparable to that of Western nations. Its victories in the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War signaled Japan’s arrival as a major player on the international stage and secured its status as the preeminent power in East Asia.

Japan’s rise as a global power was not without its challenges. The country’s rapid modernization created internal tensions between those who embraced Westernization and those who sought to preserve traditional Japanese values. These tensions would continue to shape Japan’s domestic and foreign policies well into the 20th century.

Long-term Social and Cultural Impact

The Boshin War and the subsequent reforms also had a lasting impact on Japanese society and culture. The Meiji government’s emphasis on education, industrialization, and Westernization led to the emergence of a modern, literate society that was capable of supporting Japan’s ambitions for growth and development. The new social order, which was based on merit and achievement rather than hereditary status, allowed for greater social mobility and the emergence of a new class of entrepreneurs, intellectuals, and professionals.

At the same time, the Meiji leaders sought to balance modernization with the preservation of traditional values and culture. This was reflected in the promotion of Shinto as the state religion and the reinforcement of the Emperor’s role as a symbol of national unity. The government also promoted traditional arts and crafts, while selectively adopting Western styles and practices to create a uniquely Japanese form of modernity.

Legacy of the Boshin War

The legacy of the Boshin War extends beyond its immediate political and military outcomes. It marked the end of the feudal era and began a new chapter in Japan’s history. This period was defined by rapid modernization, centralization of power, and Japan’s rise as a major global power. The war fundamentally altered the nation’s path, sparking reforms that transformed Japan from a closed, feudal society into a modern, industrial state.

The Boshin War is remembered as a time of both destruction and renewal. While it ended the samurai class and dismantled the old order, it also paved the way for a new Japan. This transformation allowed the country to become a formidable global force. Today, the war is commemorated in various historical sites, museums, and cultural works. These serve as reminders of the tumultuous yet transformative period that shaped modern Japan.

Conclusion

The Boshin War was more than a civil conflict—it was a turning point that transformed Japan’s trajectory. It marked the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate’s centuries-long rule and the dissolution of the samurai class. The war paved the way for the Meiji Restoration and the establishment of a centralized government under Emperor Meiji. With the abolition of the feudal system and sweeping political, social, and economic reforms, Japan began a rapid modernization that led it to become a global power in just a few decades.

The war’s aftermath brought significant changes. These included the dismantling of the *han* system and the creation of a modern, conscription-based military. Reforms were also made in education, law, and the economy. The Meiji government adopted Western technology and ideas but maintained elements of traditional culture. This approach shaped Japan’s unique identity during the Meiji Era.

The legacy of the Boshin War is still felt in Japan today. It remains a reminder of the nation’s capacity for reinvention and resilience during times of turmoil. The conflict’s lasting significance lies in its role in establishing a new political order and offering broader lessons on the complexities of modernization.

Understanding the Boshin War is essential to grasp how Japan transformed from a feudal society into a modern, industrialized nation. The war’s impact continues to influence Japan’s national identity and its place in the world today. From the ashes of the old order, a new Japan emerged—one that would shape the history of East Asia and beyond.