Introduction

The Sengoku era, spanning from 1467 to 1603, was a time of intense political turmoil and nearly constant warfare in Japan. This period, known as the “Warring States” era, saw powerful regional lords, or daimyo, vying for control over the country. Amid this chaos, the role of the Japanese Emperor was unique and complex.

The Emperor, traditionally seen as a divine and central figure, had his political power significantly diminished by this time. The emergence of military leaders and shogunates had shifted real political authority away from the imperial court. Despite this, the Emperor maintained a vital symbolic and cultural role.

This blog post explores the Emperor’s position during the Sengoku era, examining the historical context, the shifting power dynamics, and the Emperor’s influence on culture and religion. By understanding the Emperor’s role during this tumultuous period, we can gain deeper insights into the complexities of Japanese history and the enduring legacy of the imperial institution.

1. Historical Context of the Emperor’s Role

Understanding the historical context of the Emperor’s role during the Sengoku era requires looking back at earlier periods. The Emperor’s position evolved significantly over time, particularly from the Heian period onward.

The Emperor’s Role in the Heian Period

During the Heian period (794-1185), the Emperor held substantial political and cultural power. The court in Kyoto was the center of Japanese governance and culture. However, over time, the power of the Emperor began to wane as the Fujiwara clan and other aristocratic families gained influence.

The Shift in Power from the Emperor

By the end of the Heian period, real political power had shifted from the Emperor to the emerging military class. The establishment of the Kamakura shogunate in 1192 marked a significant decline in the Emperor’s direct control over political affairs. The shogunate, led by the shogun, became the de facto rulers of Japan.

The Emperor During the Kamakura and Muromachi Shogunates

The Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1336-1573) shogunates further solidified the Emperor’s reduced political role. While the Emperor remained the nominal head of state, the shoguns wielded actual power. The Emperor’s court continued to perform ceremonial and cultural functions but had little say in military or governmental matters.

The Emperor’s Decline in the Sengoku Era

Entering the Sengoku era, the Emperor’s political influence was at an all-time low. The country was fragmented into various domains controlled by powerful daimyo. These warlords often ignored the imperial court and pursued their ambitions independently. The Emperor’s role was largely symbolic, providing a sense of continuity and legitimacy in a time of chaos.

2. The Emperor’s Symbolic Status

During the Sengoku era, the Emperor’s political power was limited, but his symbolic status remained significant. The Emperor’s cultural and religious roles provided a sense of continuity and legitimacy in a time of turmoil.

The Emperor as a Religious and Cultural Figure

The Emperor was considered a divine descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu. This belief granted the Emperor a unique spiritual authority. The Emperor’s presence and actions were seen as vital for maintaining harmony between the spiritual and physical worlds. This divine status was a cornerstone of the Emperor’s symbolic role.

Ceremonial Duties

Despite the political chaos of the Sengoku era, the Emperor continued to perform essential ceremonial duties. These included important Shinto rituals, seasonal festivals, and rites of passage. The Emperor’s participation in these ceremonies reinforced his spiritual and cultural leadership. These rituals were crucial in maintaining the spiritual well-being of the nation.

Influence on Culture and Arts

The Emperor’s court in Kyoto remained a cultural hub during the Sengoku era. The court was a center for poetry, literature, and traditional arts. The Emperor’s patronage of these cultural activities helped preserve Japan’s rich heritage. The court’s dedication to the arts provided a sense of stability and continuity, even amidst the widespread violence.

The Emperor and the Samurai Class

While the Emperor’s political influence was limited, his symbolic status was respected by the samurai class. Many samurai viewed the Emperor as the ultimate source of legitimacy. The samurai’s loyalty to the Emperor was more symbolic than practical, but it underscored the Emperor’s enduring cultural significance. This respect for the Emperor helped maintain a sense of order and hierarchy.

The Emperor’s Role in Legitimizing Authority

Throughout the Sengoku era, the Emperor’s endorsement was sought by various daimyo. These warlords needed the Emperor’s approval to legitimize their rule. Receiving titles or decrees from the Emperor provided a veneer of traditional authority. This practice highlighted the Emperor’s continued importance in the political landscape, despite his limited direct power.

3. The Power Dynamics of the Sengoku Era

The Sengoku era was marked by complex power dynamics. The Emperor’s role during this period was shaped by the rise of regional lords and the decline of central authority.

The Rise of the Daimyo and the Emperor

During the Sengoku era, powerful regional lords, known as daimyo, controlled vast territories. These daimyo had their own armies and fortresses. They fought constant battles to expand their influence. The Emperor, however, had little control over these military leaders. Despite this, the daimyo often sought the Emperor’s endorsement to legitimize their rule.

The Emperor and Shifting Alliances

The Sengoku era was characterized by shifting alliances among the daimyo. Warlords formed and broke alliances based on their strategic interests. The Emperor’s role in these alliances was mostly symbolic. Daimyo who sought to bolster their legitimacy would sometimes seek titles or decrees from the Emperor. These imperial endorsements, while not militarily significant, carried cultural weight.

The Decline of the Shogunate and the Emperor

The Ashikaga shogunate, which had ruled Japan since the 14th century, saw its power decline during the Sengoku era. The shogunate’s weakening control allowed the daimyo to operate more independently. The Emperor, situated in Kyoto, remained a figurehead. The real power was in the hands of the regional lords. The Emperor’s court continued to perform cultural and religious duties but had minimal influence on the political landscape.

The Emperor’s Court and Cultural Influence

Despite the political chaos, the Emperor’s court in Kyoto remained a cultural beacon. The court preserved traditional arts, literature, and religious practices. The Emperor’s symbolic role helped maintain a sense of continuity and cultural identity during a time of fragmentation. The court’s cultural influence provided a counterbalance to the political power of the daimyo.

4. The Emperor’s Political Influence

The Sengoku era saw the Emperor’s political influence significantly diminished. However, the Emperor’s role was not entirely devoid of political relevance.

The Emperor’s Court in Kyoto

The Emperor’s court in Kyoto was a hub of cultural and ceremonial activities. Despite the political fragmentation, the court maintained its traditional functions. The Emperor presided over important religious ceremonies and cultural events. These activities, though symbolic, reinforced the Emperor’s position as the spiritual and cultural leader of Japan.

The Emperor’s Decrees and Titles

Even with limited political power, the Emperor’s decrees and titles were still sought by the daimyo. These endorsements from the Emperor provided a veneer of legitimacy to the warlords’ rule. Daimyo who received imperial titles could claim a connection to the ancient traditions of Japan. This connection was valuable in a time of constant warfare and shifting alliances.

Political Legitimacy

The Emperor’s role in conferring legitimacy was crucial. Warlords who aligned themselves with the Emperor could bolster their claims to power. This alignment was often more symbolic than practical, but it carried significant cultural weight. The Emperor’s endorsement could enhance a daimyo’s standing among his peers and subjects.

The Emperor’s Support and Patronage

Some daimyo sought to gain favor with the Emperor by offering support and patronage. This support could include financial contributions to the court or participation in imperial ceremonies. In return, the Emperor’s court might grant honorary titles or other forms of recognition. This exchange reinforced the Emperor’s symbolic importance, even if it did not translate into direct political power.

Limited Political Actions

There were instances where the Emperor attempted to influence political events. These attempts were often constrained by the dominant power of the daimyo. The Emperor’s appeals or interventions were typically more effective in moral or cultural terms than in changing the political landscape. Nonetheless, the Emperor’s actions were part of the broader tapestry of the Sengoku era’s power dynamics.

5. Key Emperors of the Sengoku Era

Several emperors reigned during the Sengoku era, each facing unique challenges and playing distinct roles. These key emperors navigated a complex landscape of war and political fragmentation.

Emperor Go-Hanazono (1418-1464)

Emperor Go-Hanazono reigned from 1428 to 1464, just before the Sengoku era began. His reign witnessed the early signs of the political turmoil that would define the Sengoku period. The Emperor’s influence was already waning as the Ashikaga shogunate struggled to maintain control. Despite this, Emperor Go-Hanazono maintained the imperial court’s cultural and ceremonial activities, preserving traditions during a time of growing instability.

Emperor Go-Kashiwabara (1500-1526)

Emperor Go-Kashiwabara’s reign from 1500 to 1526 was marked by significant financial difficulties and the rise of powerful daimyo. The imperial court faced severe economic constraints, limiting its ability to exert any political influence. Despite these challenges, Emperor Go-Kashiwabara worked to uphold the dignity of the imperial institution. His reign saw continued cultural contributions, even as political power remained out of reach.

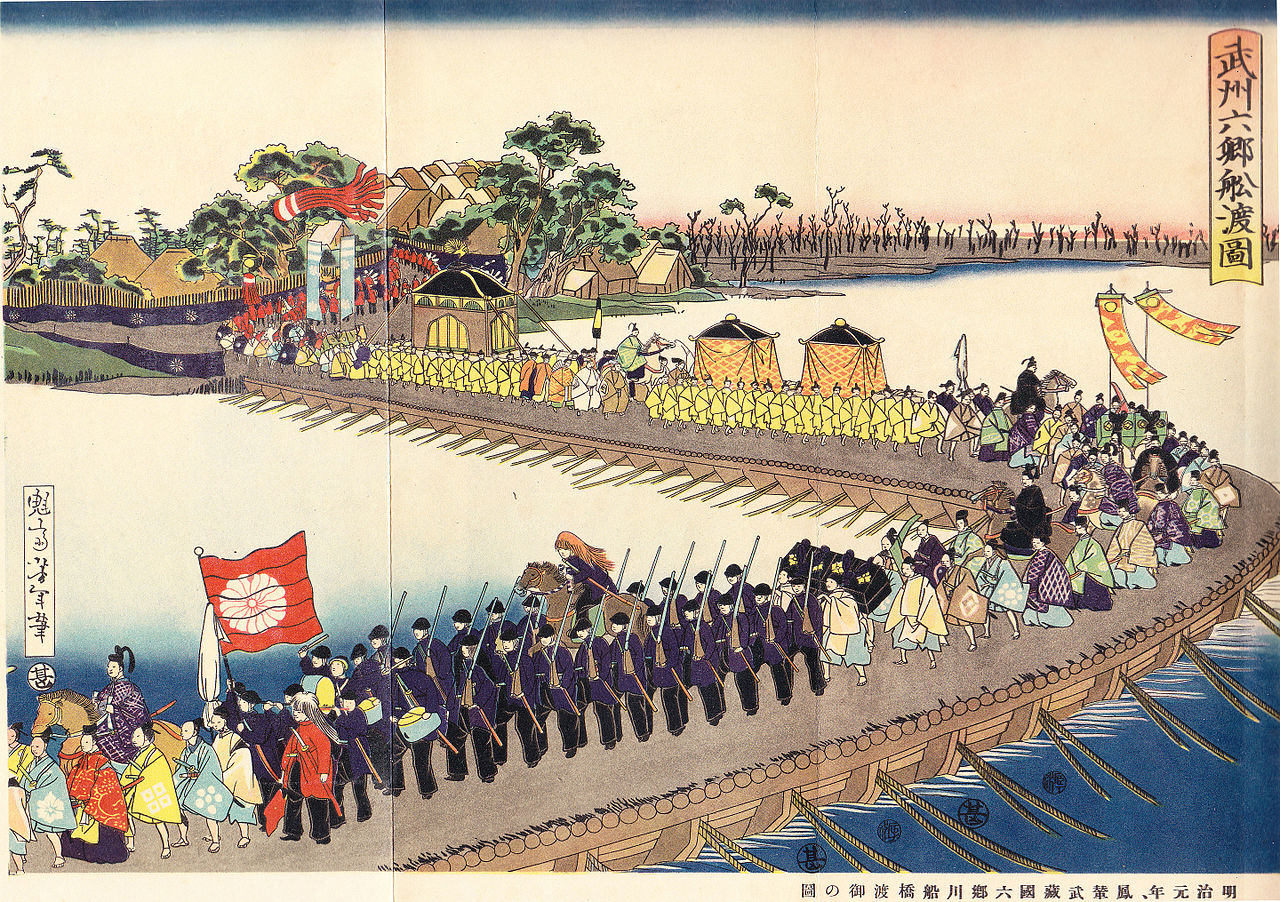

Emperor Go-Nara (1526-1557)

Emperor Go-Nara reigned from 1526 to 1557, during the height of the Sengoku era’s conflicts. His reign was characterized by efforts to navigate the complex web of daimyo alliances and rivalries. Emperor Go-Nara sought to secure support from various daimyo to stabilize the imperial court’s finances and influence. While his political power was limited, Emperor Go-Nara’s court remained a symbol of continuity and cultural heritage.

Emperor Ogimachi (1557-1586)

Emperor Ogimachi’s reign from 1557 to 1586 overlapped with significant developments in the Sengoku era. The period saw the rise of influential figures like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Emperor Ogimachi had to navigate relationships with these powerful warlords. His reign witnessed the continued decline of the shogunate’s influence and the increasing autonomy of the daimyo. Ogimachi’s court maintained its cultural and ceremonial roles, providing a sense of stability amidst the chaos.

Emperor Go-Yōzei (1586-1611)

Emperor Go-Yōzei’s reign began in 1586, towards the end of the Sengoku era. His tenure saw the unification efforts of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and later, the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate by Tokugawa Ieyasu. Emperor Go-Yōzei’s reign was marked by attempts to restore some of the imperial court’s influence and dignity. He navigated complex relationships with the emerging central powers, setting the stage for the relative stability of the Edo period.

6. The Cultural and Religious Impact

The Emperor’s role during the Sengoku era was not just political but also deeply cultural and religious. Despite the chaos, the Emperor’s court remained a beacon of tradition and spirituality.

The Emperor and Buddhism

Buddhism played a significant role in the Emperor’s court. The imperial family had long been patrons of Buddhist temples and monasteries. During the Sengoku era, the Emperor continued to support Buddhist practices and institutions. This support helped preserve Buddhist traditions and teachings amidst the widespread violence. The Emperor’s patronage of Buddhism also reinforced the connection between the imperial family and spiritual authority.

The Emperor and Shinto Beliefs

Shintoism, the indigenous religion of Japan, was central to the Emperor’s divine status. The Emperor was considered a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu. This belief granted the Emperor a unique spiritual authority. During the Sengoku era, the Emperor performed key Shinto rituals and ceremonies. These practices were essential in maintaining the spiritual and cultural continuity of the nation. His role in Shintoism provided a sense of stability and divine legitimacy.

The Emperor’s Influence on Arts and Culture

Throughout the Sengoku era, the Emperor’s court in Kyoto remained a cultural hub. Despite the political fragmentation, the court continued to patronize the arts. Poetry, literature, and traditional music thrived under the Emperor’s influence. The imperial court’s dedication to cultural preservation ensured that Japanese artistic traditions survived the turmoil. The Emperor’s support for the arts was a crucial factor in maintaining the nation’s cultural heritage.

The Emperor and Neo-Confucianism

Neo-Confucianism also impacted the Emperor’s court during the Sengoku era. This philosophical movement emphasized moral integrity, social order, and respect for hierarchy. The Emperor’s court adopted Neo-Confucian ideals, which influenced governance and education. These principles reinforced the Emperor’s role as a moral and ethical leader. The integration of Neo-Confucianism helped shape the cultural and intellectual landscape of the time.

Cultural Legacy

The cultural impact of the Emperor during the Sengoku era extended beyond his lifetime. The traditions and practices upheld by the Emperor’s court influenced future generations. The preservation of arts, literature, and religious practices contributed to the nation’s cultural continuity. The Emperor’s cultural and religious influence provided a foundation for Japan’s identity, even during periods of upheaval.

7. The End of the Sengoku Era and the Restoration of Imperial Power

The end of the Sengoku era marked significant changes in Japan’s political landscape. The Emperor’s role evolved as the country moved towards unification and the restoration of a more centralized authority.

The Unification Under Oda Nobunaga

Oda Nobunaga played a crucial role in ending the chaos of the Sengoku era. He was a powerful daimyo who sought to unify Japan under his rule. Nobunaga recognized the symbolic importance of the Emperor. He sought the Emperor’s endorsement to legitimize his campaigns. In 1568, Nobunaga marched into Kyoto and installed Ashikaga Yoshiaki as shogun. This move strengthened Nobunaga’s position and restored some order to the imperial court.

The Emperor and Toyotomi Hideyoshi

After Nobunaga’s death, Toyotomi Hideyoshi continued the unification efforts. Hideyoshi also sought the Emperor’s approval to legitimize his rule. In 1586, he received the title of Kampaku (Imperial Regent) from the Emperor. This title elevated Hideyoshi’s status and reinforced his authority. Hideyoshi’s relationship with the Emperor helped stabilize the country and further the process of unification. The Emperor’s symbolic support was crucial in consolidating Hideyoshi’s power.

The Emperor and Tokugawa Ieyasu

Following Hideyoshi’s death, Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged as the dominant figure. In 1603, Ieyasu was appointed shogun by the Emperor. This marked the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate, which would rule Japan for over 250 years. Ieyasu’s appointment was a significant event, as it symbolized the restoration of centralized authority. The Emperor’s endorsement was essential in legitimizing Ieyasu’s rule. Although still largely symbolic, the Emperor’s role was vital in establishing the new political order.

The Emperor’s Role in the Tokugawa Shogunate

Under the Tokugawa shogunate, the Emperor’s political power remained limited. However, the shogunate recognized the importance of the Emperor’s cultural and religious influence. The Tokugawa shoguns maintained the imperial court and supported its ceremonial functions. The Emperor’s court continued to play a key role in preserving Japanese traditions. This support helped maintain the Emperor’s status as a cultural and spiritual leader.

The Restoration of Imperial Power

The restoration of imperial power began long after the Sengoku era, culminating in the Meiji Restoration of 1868. During the Meiji Restoration, the Emperor’s political authority was fully restored. The Emperor became the central figure in Japan’s modernization efforts. The foundations laid during the Sengoku era, where the Emperor’s symbolic importance was recognized, played a part in this restoration. The Emperor’s enduring cultural and spiritual influence provided a basis for reclaiming political power.

Conclusion

The Sengoku era was a time of profound chaos and transformation in Japan. Amidst the relentless battles and shifting alliances, the role of the Emperor remained a cornerstone of cultural and spiritual continuity. Although the Emperor’s political power had diminished significantly, his symbolic importance endured.

The Emperor’s court in Kyoto served as a cultural beacon, preserving traditions, arts, and religious practices. The support and endorsement of the Emperor were sought by powerful daimyo like Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu to legitimize their rule. This symbolic legitimacy was crucial in their efforts to unify Japan and establish centralized authority.

Key emperors during the Sengoku era, such as Emperor Go-Hanazono, Emperor Go-Kashiwabara, Emperor Go-Nara, Emperor Ogimachi, and Emperor Go-Yōzei, navigated the complexities of their time with resilience. They maintained the dignity and cultural significance of the imperial institution, even when political influence was limited.

The end of the Sengoku era and the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate marked a new chapter in Japan’s history. The Emperor’s role evolved, paving the way for the eventual restoration of full imperial power during the Meiji Restoration. The enduring legacy of the Emperor’s cultural and spiritual influence provided a foundation for Japan’s modernization and transformation into a unified nation.

The Emperor’s journey through the Sengoku era is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the imperial institution. It highlights the intricate balance between symbolic importance and political power, underscoring the Emperor’s lasting impact on Japanese history and culture.

References

- Berry, Mary Elizabeth. The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto. University of California Press, 1994.

- An in-depth analysis of the cultural and social changes in Kyoto during the Sengoku era.

- Brown, Delmer M., and Ichirō Ishida, eds. The Future and the Past: A Translation and Study of the Gukanshō, an Interpretive History of Japan Written in 1219. University of California Press, 1979.

- Provides historical context on the evolution of the Emperor’s role leading up to the Sengoku era.

- Hall, John Whitney. Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times. University of Michigan Press, 1970.

- A comprehensive overview of Japanese history, including detailed sections on the Sengoku era and the role of the Emperor.

- Sansom, George. A History of Japan, 1334-1615. Stanford University Press, 1961.

- An authoritative account of Japanese history covering the transition from the Ashikaga shogunate to the Tokugawa shogunate, with insights into the Emperor’s role.

- Varley, H. Paul. Warriors of Japan as Portrayed in the War Tales. University of Hawaii Press, 1994.

- Examines the lives and actions of the samurai and daimyo during the Sengoku era, providing context for the Emperor’s position.

- Wakita, Osamu. The Rise of an Urban Culture: The Culture of the Edo Period. Kodansha, 1989.

- Discusses the cultural developments during the transition from the Sengoku era to the Tokugawa shogunate, highlighting the Emperor’s influence.

- Farris, William Wayne. Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500-1300. Harvard University Asia Center, 1992.

- Explores the early evolution of Japan’s military and the shifting power dynamics that set the stage for the Sengoku era.

- Totman, Conrad. A History of Japan. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005.

- Provides a detailed narrative of Japanese history, including the Sengoku era and the role of the Emperor.

- McCullough, Helen Craig. The Taiheiki: A Chronicle of Medieval Japan. Columbia University Press, 1959.

- Chronicles the events of medieval Japan, offering insights into the imperial court’s activities and influence.

- Jansen, Marius B. The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Discusses the impact of the Sengoku era on the formation of modern Japan, with references to the Emperor’s evolving role.

Additional Resources

- Books:

- “Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912” by Donald Keene: A detailed account of Emperor Meiji’s life and the restoration of imperial power, providing context for the long-term impacts of the Sengoku era.

- “Samurai Revolution: The Dawn of Modern Japan Seen Through the Eyes of the Shogun’s Last Samurai” by Romulus Hillsborough: Explores the transition from the Sengoku era to the Meiji Restoration, focusing on the samurai class and their relationship with the Emperor.

- “Japan’s Medieval Population: Famine, Fertility, and Warfare in a Transformative Age” by William Wayne Farris: Analyzes demographic changes and their effects on political and social structures, including the Emperor’s role.

- Documentaries:

- “Samurai Japan: A Journey Back in Time”: This documentary explores the Sengoku era, focusing on the lives of the samurai and the Emperor’s influence on the era’s culture and politics.

- “Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire”: A PBS documentary series that covers the history of Japan, including the Sengoku era and the restoration of the Emperor’s power during the Meiji Restoration.

- Articles:

- “The Sengoku Era: An Age of Warring States” by Stephen Turnbull: An article providing an overview of the Sengoku era, discussing the major daimyo and the Emperor’s role.

- “Cultural Patrons of the Sengoku Era: The Imperial Court and Its Influence”: Explores the cultural contributions of the Emperor’s court during the Sengoku period.

- Websites:

- Japanese Historical Text Initiative (JHTI): A digital archive of historical texts, providing primary sources related to the Sengoku era and the Emperor.

- The Samurai Archives: An online resource with articles, biographies, and primary sources about the Sengoku era, including information on the Emperor’s role.

- National Diet Library of Japan: Offers access to historical documents and manuscripts from the Sengoku era, including records related to the imperial court.

- Academic Journals:

- “Monumenta Nipponica”: A scholarly journal with articles on Japanese history, including studies on the Emperor’s role during the Sengoku era.

- “The Journal of Japanese Studies”: Publishes research on various aspects of Japanese history, culture, and politics, with relevant articles on the Sengoku era.

- Online Courses:

- “History of Japan: From the Sengoku Era to the Meiji Restoration” on Coursera: Offers a comprehensive overview of Japanese history, including detailed lectures on the Emperor’s role.

- “Samurai and the Warrior Culture of Japan” on edX: Explores the samurai culture and the political landscape of the Sengoku era, highlighting the Emperor’s influence.

These additional resources provide a wealth of information for anyone interested in learning more about the Emperor’s role during the Sengoku era and its lasting impact on Japanese history and culture.

![Emperor Go-Nara (後奈良天皇, Go-Nara-tennō, January 26, 1495 – September 27, 1557)[1] was the 105th Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Role of the japanese Emperor during the Sengoku Era.](https://sengokuchronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1260px-Emperor_Go-Nara-e1715746159363-1024x667.jpg)