Introduction

The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 stands as one of the most significant and dramatic events in Japanese history, marking the definitive end of the samurai era and the solidification of the Meiji government’s power. This armed revolt, led by the disenchanted samurai Saigō Takamori, was a culmination of deep-seated tensions between the rapidly modernizing Japanese state and the traditional warrior class that had dominated for centuries.

In this blog post, we will delve into the causes and background of the rebellion, explore the life and motivations of Saigō Takamori, and recount the key battles and events that defined the conflict. We will also examine the aftermath and lasting impact of the rebellion on Japanese society and its historical legacy. Through this exploration, we aim to understand not only the historical facts but also the cultural and social shifts that this rebellion epitomized.

Join us as we journey back to a pivotal moment in Japan’s transformation from a feudal society to a modern nation, and uncover the story of the last samurai who dared to defy the tides of change.

Background and Causes

The roots of the Satsuma Rebellion lie in the sweeping changes initiated by the Meiji Restoration, which began in 1868. The Meiji government embarked on an ambitious project to modernize Japan, transforming it from a feudal society into a centralized, industrialized nation capable of standing toe-to-toe with Western powers. This period of rapid modernization, while essential for Japan’s future success, created significant upheaval and discontent, particularly among the samurai class.

The Meiji Restoration and Modernization

The Meiji Restoration marked the end of over 250 years of Tokugawa shogunate rule and the beginning of the Meiji Era. The new government implemented a series of reforms aimed at dismantling the old feudal order. Key among these reforms was the abolition of the han system (feudal domains) and the establishment of a centralized government. This shift was intended to unify Japan under a strong central authority, essential for its modernization efforts.

In addition to political centralization, the Meiji government pursued economic and military modernization. They sought to adopt Western technology and organizational methods, which included the establishment of a conscripted army. This new military force was designed to replace the samurai, who had traditionally served as the warrior class.

Impact on the Samurai

The samurai, who had enjoyed significant social and economic privileges under the old feudal system, found themselves increasingly marginalized in the new order. Their stipends, which were their primary source of income, were gradually reduced and eventually replaced with government bonds. This transition led to financial difficulties for many samurai, who struggled to adapt to the new economic realities.

Furthermore, the government issued a series of edicts that stripped the samurai of their traditional privileges. The most symbolic of these was the prohibition against carrying swords in public, which effectively nullified their status as warriors. The disbanding of their domains and the loss of their stipends compounded their sense of disenfranchisement.

Saigō Takamori: The Reluctant Rebel

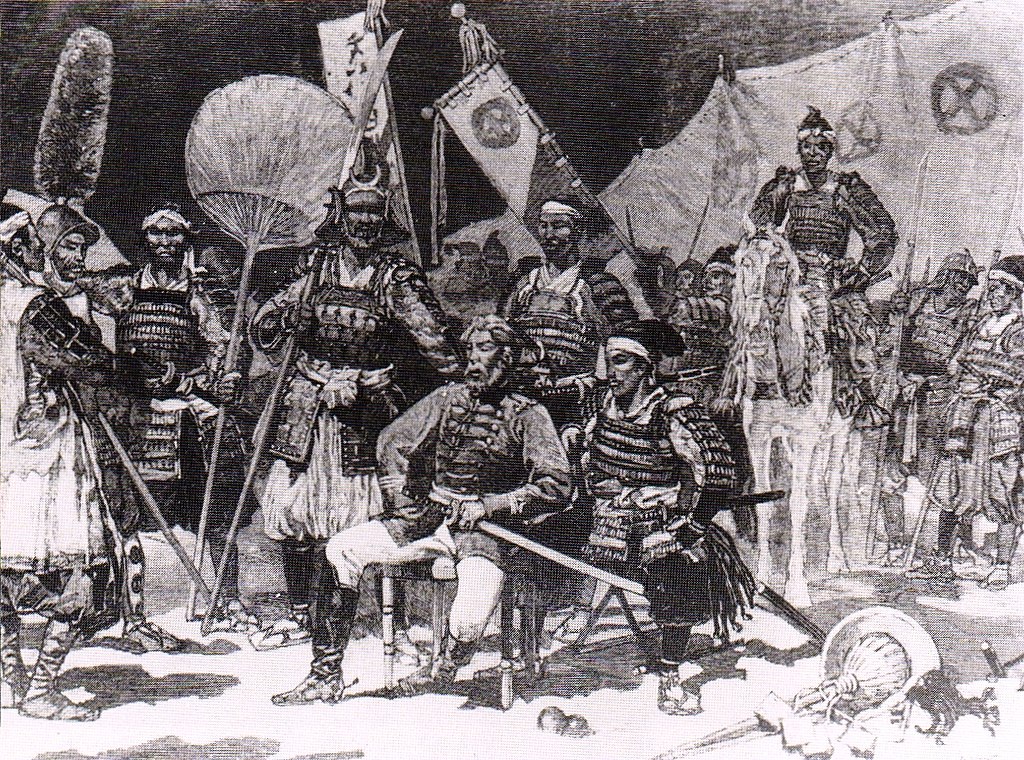

Saigō Takamori stands as one of the most iconic figures in Japanese history, often referred to as the “last true samurai.” His life and legacy are deeply intertwined with the Satsuma Rebellion, which he led against the very government he helped to establish. Understanding Saigō’s motivations and his journey from a loyal supporter of the Meiji Restoration to a reluctant rebel is crucial to grasping the full context of the rebellion.

Early Life and Rise to Prominence

Saigō Takamori was born in 1828 in the Satsuma Domain (present-day Kagoshima Prefecture), a region known for its strong samurai traditions and fierce independence. He came from a modest samurai family but quickly rose through the ranks due to his talent and dedication. By the 1860s, Saigō had become a key figure in the Satsuma leadership and a staunch advocate for the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Role in the Meiji Restoration

Saigō played a pivotal role in the Meiji Restoration, which aimed to restore imperial rule and modernize Japan. He was instrumental in forming alliances with other powerful domains, such as Chōshū, and leading the military campaigns that ultimately dismantled the shogunate. Saigō’s efforts helped pave the way for the establishment of the Meiji government, and he was regarded as a national hero.

Disillusionment with the Meiji Government

Despite his significant contributions, Saigō grew increasingly disillusioned with the direction of the new government. The rapid Westernization and modernization efforts, which included the abolition of the samurai class’s privileges and the establishment of a conscripted army, troubled him deeply. Saigō believed that these changes were eroding Japan’s traditional values and identity.

In 1873, Saigō resigned from his government positions and returned to Satsuma. There, he established a private academy that became a focal point for disaffected samurai. The academy was not only a place of learning but also a hub for those who opposed the government’s policies and sought to preserve the samurai way of life.

The Path to Rebellion

Tensions between the government and the samurai in Satsuma continued to escalate. Saigō’s influence and the growing anti-government sentiment among his followers made the situation increasingly volatile. Rumors that the government planned to arrest Saigō and other leaders further inflamed the situation. Whether these rumors were based on fact or were a catalyst created by his supporters to incite action, they were enough to push the samurai to rebellion.

The Rebellion Begins

The Satsuma Rebellion erupted in February 1877, marking a significant and bloody conflict between the disenchanted samurai led by Saigō Takamori and the modernizing Meiji government. This section will detail the initial stages of the rebellion, the motivations of the rebels, and the early confrontations that set the stage for the subsequent battles.

The March to Kumamoto Castle

The rebellion officially began when Saigō Takamori and approximately 12,000 samurai marched from Kagoshima towards Kumamoto Castle. This march was a bold and defiant move, directly challenging the Meiji government’s authority. The samurai were fueled by a mix of resentment over their declining status and a deep-seated loyalty to traditional Japanese values, which they believed the Meiji government was undermining.

The choice of Kumamoto Castle as their first target was strategic. The castle was one of the most fortified and important military outposts in Kyushu, and capturing it would have provided the rebels with a significant stronghold and a morale boost. However, it also represented a formidable challenge, as it was well-defended by government forces.

Initial Successes and Setbacks

As Saigō’s forces approached Kumamoto, they encountered resistance from the castle’s garrison. Despite their initial numerical superiority, the samurai faced several challenges. The castle’s defenders, well-equipped and trained in modern military tactics, mounted a strong defense. The siege of Kumamoto Castle quickly turned into a protracted and grueling conflict.

During the early days of the rebellion, the samurai achieved some tactical victories. They managed to engage government forces in several skirmishes, demonstrating their combat skills and determination. However, the inability to capture Kumamoto Castle became a significant setback. The prolonged siege drained the rebels’ resources and sapped their momentum.

Government Response

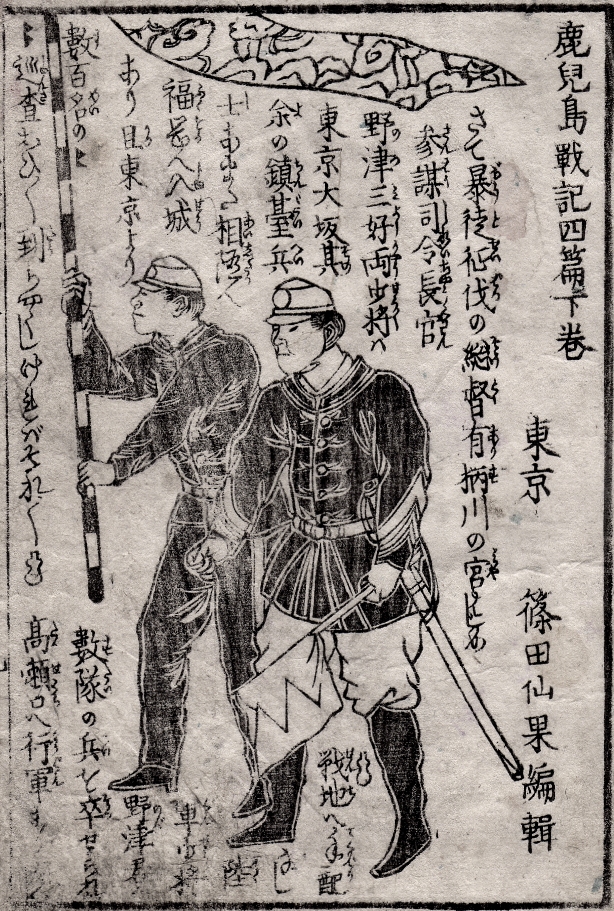

The Meiji government, recognizing the threat posed by the rebellion, mobilized its forces swiftly and decisively. General Yamagata Aritomo was appointed to lead the government’s military response. Under his command, a conscripted army of approximately 60,000 soldiers was assembled to suppress the rebellion.

The government’s forces, equipped with modern weapons and supported by Western military advisors, had a distinct advantage over the samurai, who were primarily armed with traditional weapons and limited modern artillery. The disparity in resources and technology would play a crucial role in the unfolding conflict.

Major Battles and Key Events

The Satsuma Rebellion was characterized by a series of significant battles and key events that defined the conflict between Saigō Takamori’s samurai forces and the Meiji government’s modern army. These engagements highlighted the struggle between traditional samurai values and the emergent modern state.

Siege of Kumamoto Castle

The rebellion’s first major event was the siege of Kumamoto Castle. Saigō Takamori and his forces began the siege in February 1877, hoping to capture this strategic stronghold. Despite initial successes, the siege turned into a protracted and grueling confrontation. The castle’s defenders, well-armed with modern weaponry, managed to hold out against the samurai, whose resources were quickly depleting. The prolonged siege became a significant drain on Saigō’s forces and marked a critical early setback for the rebellion.

Battle of Tabaruzaka

One of the rebellion’s most decisive battles occurred at Tabaruzaka in March 1877. This battle was crucial for both sides, as it was key to controlling access to Kumamoto. The government forces, led by General Yamagata Aritomo, aimed to relieve the besieged Kumamoto Castle by breaking through the samurai’s defensive lines. The battle saw intense and bloody fighting, with heavy casualties on both sides. Despite their valiant efforts, Saigō’s forces were ultimately defeated, allowing government troops to lift the siege of Kumamoto Castle. This defeat marked a significant turning point, weakening the rebel forces and diminishing their chances of victory.

Battle of Wadagoe

Following the loss at Tabaruzaka, Saigō’s forces attempted to regroup and continue their resistance. In April 1877, they engaged government forces at the Battle of Wadagoe. This battle was characterized by guerrilla tactics employed by the samurai, leveraging their knowledge of the local terrain to conduct surprise attacks. However, the government’s numerical and technological superiority once again prevailed. The defeat at Wadagoe further demoralized the samurai and highlighted the growing disparity between the two sides.

Battle of Miyakonojo

As the rebellion continued, Saigō’s forces sought to regain their momentum by attacking government positions in southern Kyushu. The Battle of Miyakonojo in June 1877 was another significant engagement. The samurai aimed to capture the town and secure a strategic advantage. Despite their efforts, government forces, reinforced and better equipped, managed to repel the attack. The failure at Miyakonojo underscored the rebels’ dwindling resources and the increasing difficulty of sustaining the rebellion.

Battle of Nobeoka

In August 1877, the Battle of Nobeoka saw the samurai make a last-ditch effort to turn the tide of the conflict. Saigō’s forces, significantly reduced and suffering from supply shortages, faced the government’s well-organized troops. The battle ended in a decisive defeat for the rebels, forcing them to retreat towards Kagoshima. This retreat marked the beginning of the end for the Satsuma Rebellion, as the government tightened its grip on the remaining samurai strongholds.

The Final Stand and Saigō’s Fate

The Satsuma Rebellion reached its dramatic and tragic conclusion at the Battle of Shiroyama in September 1877. This final stand of Saigō Takamori and his remaining samurai against the overwhelming forces of the Meiji government epitomized the end of an era and the fierce, unyielding spirit of the samurai class.

Retreat to Shiroyama

After the decisive defeats at previous battles, Saigō Takamori and his remaining followers were forced to retreat to their homeland of Kagoshima. With their numbers dwindled to around 500 and resources nearly exhausted, the samurai fortified themselves on Shiroyama, a hill overlooking Kagoshima Bay. Surrounded by government forces, Saigō and his men prepared for a final, desperate stand.

The Siege of Shiroyama

General Yamagata Aritomo, leading the government troops, was determined to end the rebellion once and for all. He deployed approximately 30,000 soldiers equipped with modern weaponry, including artillery and Gatling guns, to encircle Shiroyama and cut off any potential escape routes for the rebels. The government forces began bombarding the samurai’s position, further depleting their already scarce supplies and ammunition.

The Final Battle

On the night of September 24, 1877, under the cover of darkness, Saigō Takamori and his men launched a final, desperate charge against the government forces. This act of courage and defiance was emblematic of the samurai ethos of honor and bravery. Despite being vastly outnumbered and outgunned, the samurai fought fiercely, inflicting significant casualties on the government troops.

As the battle raged on, the inevitable outcome became clear. Saigō Takamori, severely wounded during the charge, was carried by his remaining loyal followers to a secluded spot on the hillside. According to popular accounts, Saigō chose to end his life through seppuku (ritual suicide), maintaining his honor in the face of certain defeat. This act has become a symbol of the samurai’s unwavering commitment to their principles, even in the face of insurmountable odds.

Aftermath and Impact

The aftermath of the Satsuma Rebellion had profound and far-reaching consequences for Japan, marking the end of an era and paving the way for the country’s modernization and transformation. The defeat of the samurai and the consolidation of the Meiji government’s power ushered in a new phase in Japanese history.

Consolidation of the Meiji Government’s Power

The rebellion’s suppression demonstrated the Meiji government’s ability to maintain control and enforce its modernization policies. The victory solidified the authority of the central government and marked a decisive end to the feudal domain system. The government’s success in quelling the rebellion sent a clear message that resistance to its reforms would not be tolerated.

End of the Samurai Class

The defeat of the Satsuma Rebellion marked the definitive end of the samurai as a distinct social class. The samurai, who had been the ruling military elite for centuries, were now fully integrated into the broader society. The abolition of their stipends, the prohibition of carrying swords, and the establishment of a conscripted army effectively dissolved the samurai class. Many former samurai transitioned into roles as bureaucrats, teachers, or businessmen, adapting to the new social and economic order.

Military and Social Reforms

The Satsuma Rebellion highlighted the need for continued military and social reforms in Japan. The government recognized the importance of modernizing its military further to prevent future uprisings and to defend against external threats. The conscripted army, equipped with modern weapons and trained in Western military tactics, became the backbone of Japan’s defense forces.

On a social level, the rebellion underscored the necessity of integrating traditional values with modern ideals. The government pursued policies that promoted education, industrialization, and infrastructure development, laying the foundation for Japan’s rapid modernization and economic growth.

Economic Impact

The rebellion had significant economic implications. The cost of suppressing the rebellion strained the government’s finances, leading to increased taxation and efforts to expand the national economy. The government accelerated its industrialization policies, promoting the development of railways, factories, and telecommunication networks. These efforts aimed to create a robust, modern economy capable of competing with Western powers.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

The legacy of the Satsuma Rebellion and Saigō Takamori’s martyrdom had a lasting cultural impact. Saigō was posthumously pardoned and became a symbol of loyalty, bravery, and resistance to unwanted change. His story was romanticized in literature, theater, and later, film, embodying the spirit of the samurai in popular culture. The rebellion itself came to symbolize the struggle between tradition and progress, a theme that resonated deeply within Japanese society.

Legacy

The legacy of the Satsuma Rebellion and Saigō Takamori extends far beyond the immediate aftermath of the conflict, leaving a lasting imprint on Japanese culture, society, and national identity. This section explores the multifaceted legacy of the rebellion and its enduring significance in Japan.

Saigō Takamori: The Last Samurai

Saigō Takamori, often hailed as the “last true samurai,” has become a cultural icon in Japan. His life, characterized by unwavering loyalty, bravery, and adherence to traditional values, continues to be celebrated and romanticized. Saigō’s role in the Satsuma Rebellion and his ultimate sacrifice have cemented his status as a symbol of resistance against the loss of cultural identity and the encroachments of modernization.

Cultural Representations

Saigō’s story and the Satsuma Rebellion have been immortalized in various forms of Japanese art and literature. Novels, plays, and films have depicted Saigō’s heroic yet tragic life, contributing to his legendary status. Notable works, such as Mori Ōgai’s novel “The Last Samurai” and the popular NHK Taiga drama series “Segodon,” have brought Saigō’s story to a broad audience, ensuring that his legacy endures in the public consciousness.

Symbol of Resistance and Honor

The Satsuma Rebellion, though ultimately a failed insurrection, has come to symbolize the struggle between tradition and progress. It represents the fierce resistance of the samurai to the sweeping changes imposed by the Meiji government. Saigō’s decision to lead the rebellion, despite knowing the overwhelming odds against him, is often seen as the ultimate act of honor and loyalty to his beliefs and way of life.

Influence on Modern Japan

The themes of the Satsuma Rebellion—loyalty, honor, and resistance to change—continue to resonate in contemporary Japan. The rebellion serves as a historical reminder of the complexities and challenges associated with rapid modernization. It underscores the importance of maintaining cultural heritage and identity while embracing progress and innovation.

Memorials and Monuments

Saigō Takamori’s legacy is physically manifested in numerous memorials and monuments across Japan. One of the most famous is the statue of Saigō in Ueno Park, Tokyo, which depicts him in traditional samurai attire, walking his dog. This statue has become a popular cultural landmark, symbolizing the enduring respect and admiration for Saigō and his values.

Historical Lessons

The Satsuma Rebellion offers valuable lessons on the importance of balanced reform and the potential consequences of alienating significant social groups. The rebellion highlighted the risks of implementing rapid and radical changes without adequately addressing the concerns of those affected. This historical lesson has informed subsequent policy decisions in Japan, emphasizing the need for inclusive and considered approaches to modernization.

Conclusion

The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 stands as a pivotal chapter in Japanese history, symbolizing the intense conflict between tradition and modernization that characterized the Meiji period. Led by Saigō Takamori, the rebellion marked the final stand of the samurai against the sweeping changes implemented by the Meiji government. Though ultimately unsuccessful, the rebellion and its aftermath had profound and lasting impacts on Japan’s social, political, and cultural landscape.

Saigō Takamori, remembered as the “last true samurai,” has become an enduring symbol of loyalty, honor, and resistance to change. His legacy, along with the events of the rebellion, continues to resonate in Japanese culture, serving as a reminder of the complexities and sacrifices involved in the nation’s journey toward modernization.

The Satsuma Rebellion also provided critical lessons on the importance of balanced and inclusive reforms, highlighting the potential consequences of alienating significant segments of society during periods of rapid transformation. The rebellion’s legacy underscores the need to preserve cultural identity while embracing progress, a theme that remains relevant in contemporary Japan.

As we reflect on the Satsuma Rebellion, we gain a deeper understanding of the historical forces that shaped modern Japan and the enduring values that continue to influence its national identity. The story of Saigō Takamori and the samurai’s last stand serves as a poignant reminder of the enduring spirit of the samurai and the timeless struggle between tradition and innovation.

Additional Resources

For those interested in delving deeper into the Satsuma Rebellion, Saigō Takamori, and the broader context of Japan’s Meiji period, the following resources offer comprehensive and insightful information:

Books

- “The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori” by Mark Ravina

- This biography provides an in-depth look at the life of Saigō Takamori, exploring his role in the Meiji Restoration and the Satsuma Rebellion.

- “The Meiji Restoration” by W.G. Beasley

- A detailed account of the Meiji Restoration, this book offers a thorough understanding of the political and social changes that set the stage for the Satsuma Rebellion.

- “Samurai Revolution: The Dawn of Modern Japan Seen Through the Eyes of the Shogun’s Last Samurai” by Romulus Hillsborough

- This book provides a narrative of the samurai’s transformation during the Meiji era, including the Satsuma Rebellion.

- “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964” by Ian Buruma

- A broader look at Japan’s transformation from the late Edo period through the post-World War II era, including the impact of the Satsuma Rebellion.

Articles and Papers

- “The Satsuma Rebellion of 1877: From Kagoshima to Kumamoto” by Charles L. Yates

- A scholarly article examining the key events and significance of the Satsuma Rebellion.

- “Saigō Takamori and the Samurai Revolution in Japan” by Ivan Morris

- An analysis of Saigō Takamori’s influence on the samurai class and the Meiji Restoration.

Documentaries and Videos

- “Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire” (PBS)

- This documentary series explores the history of Japan, including the Meiji Restoration and the Satsuma Rebellion.

- “Samurai Rebellion: The Last Stand of Saigō Takamori” (History Channel)

- A detailed documentary focusing on the life of Saigō Takamori and the events of the Satsuma Rebellion.

- NHK Taiga Drama “Segodon”

- A historical drama series that portrays the life of Saigō Takamori, offering a dramatized but informative view of his contributions and the rebellion.

Online Resources

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Satsuma Rebellion

- A concise overview of the Satsuma Rebellion, its causes, and its impact on Japanese history.

- Japan History Online: Saigō Takamori and the Satsuma Rebellion

- An online resource providing detailed articles and timelines related to Saigō Takamori and the rebellion.

- National Diet Library Digital Collections

- Access to historical documents, books, and resources related to the Meiji period and the Satsuma Rebellion.

These resources provide a comprehensive starting point for anyone interested in exploring the complexities and significance of the Satsuma Rebellion and its lasting legacy in Japanese history.