Introduction

The Tokugawa Shogunate, also known as the Edo period, represents a critical era in Japanese history, spanning over 250 years from 1603 to 1868. This period, characterized by peace, stability, and isolation, was marked by the rule of the Tokugawa family, who established a feudal military government that controlled Japan with an iron fist.

The significance of the Tokugawa Shogunate lies in its transformative impact on Japan’s political, social, and cultural landscapes. Under the shogunate’s rule, Japan saw the unification of its fractured domains, the establishment of a rigid social hierarchy, and the development of a thriving economy despite the country’s self-imposed isolation from much of the outside world. This era also witnessed a flourishing of arts and culture, setting the stage for the modernization of Japan in the subsequent Meiji era.

Understanding the Tokugawa Shogunate is crucial for comprehending the foundation upon which modern Japan was built. From its rise under Tokugawa Ieyasu following the Battle of Sekigahara to its decline in the face of internal strife and external pressures, the story of the Tokugawa Shogunate is a fascinating journey through one of Japan’s most influential periods. This blog post will delve into the political structure, social hierarchy, economic policies, cultural developments, and the eventual decline of the Tokugawa Shogunate, providing a comprehensive overview of this pivotal era in Japanese history.

Historical Background

The Sengoku Period: Japan Before the Tokugawa Shogunate

Before the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan was engulfed in a period of intense social upheaval and constant military conflict known as the Sengoku, or Warring States, period (1467-1603). This era was marked by the fragmentation of power among various feudal lords, or daimyos, each vying for control over different regions of Japan. The absence of a central authority led to a series of conflicts and shifting alliances, creating a chaotic and unstable political landscape.

The Path to Unification: Key Figures and Events

The path to unification began with three significant figures: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582)

Oda Nobunaga was a ruthless and innovative military leader who initiated the process of consolidating power. His strategic use of firearms and innovative tactics allowed him to defeat many rival clans and lay the groundwork for unification. However, Nobunaga’s sudden death in 1582 left his work unfinished.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Nobunaga’s loyal general, succeeded him and continued the campaign to unify Japan. Hideyoshi’s efforts brought most of the country under his control, but he failed to secure a lasting legacy due to the lack of a strong successor. His death in 1598 left a power vacuum, setting the stage for the final phase of unification.

The Rise of Tokugawa Ieyasu

Early Life and Alliances

Tokugawa Ieyasu was a powerful daimyo and shrewd strategist who had long been a key ally and vassal under both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi. Carefully consolidating his power base in the Kanto region, Ieyasu was well-positioned to seize control.

The Battle of Sekigahara (1600)

The turning point came at the Battle of Sekigahara, a massive and decisive conflict between rival factions. Ieyasu’s victory at Sekigahara effectively ended the warring states period, allowing him to eliminate his rivals and solidify his dominance.

Establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate

Appointment as Shogun

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed Shogun by the Emperor, officially establishing the Tokugawa Shogunate. This marked the beginning of the Edo period, named after the shogunate’s capital, Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

Centralized Feudal System

The Tokugawa Shogunate implemented a centralized feudal system that maintained strict control over the daimyos and enforced a rigid social order. This era of relative peace and stability, known as the Pax Tokugawa, allowed for significant economic growth, cultural development, and the establishment of a distinctly Japanese identity.

Isolation and Stability

Sakoku Policy

One of the defining features of the Tokugawa Shogunate was its isolationist policies. The Sakoku edict, or “closed country” policy, limited foreign influence and trade, ensuring that Japan remained insulated from external pressures and influences. This policy contributed to the stability and longevity of the shogunate but also set the stage for challenges in the mid-19th century.

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s establishment marked a pivotal moment in Japanese history, transforming the country’s political, social, and economic landscape and leaving a legacy that would shape Japan for generations to come. The unification under Tokugawa Ieyasu and the subsequent era of peace and stability provided the foundation for Japan’s development into a modern nation.

The Political Structure of the Tokugawa Shogunate

The Role of the Shogun

At the apex of the Tokugawa Shogunate’s political structure was the Shogun, the military ruler who held the ultimate authority in Japan. The Shogun was responsible for maintaining order, enforcing laws, and overseeing the administration of the entire country. Although the Emperor remained the ceremonial and spiritual leader of Japan, his powers were largely symbolic during this period, with the Shogun wielding the actual political and military power.

The Bakuhan System

Centralized Feudalism

The Tokugawa Shogunate established a centralized feudal system known as the Bakuhan system, which was a blend of central and feudal governance. The term “Bakuhan” combines “bakufu” (the Shogunate’s military government) and “han” (domains controlled by the daimyos).

Daimyos and Their Domains

Under the Bakuhan system, the country was divided into numerous domains, each governed by a daimyo. These powerful feudal lords were required to pledge loyalty to the Shogun and manage their territories according to the Shogunate’s laws and policies. In return, they were granted a degree of autonomy within their domains, as long as they maintained order and paid taxes to the central government.

Administrative Divisions and Governance

Hans (Domains)

The domains, or hans, were classified based on their size and productivity, which determined the daimyo’s wealth and influence. The Shogunate carefully balanced the power of the daimyos to prevent any single lord from becoming too powerful.

Sankin-kotai (Alternate Attendance System)

One of the key mechanisms for maintaining control over the daimyos was the Sankin-kotai system. This policy required daimyos to spend alternating years in the capital, Edo, and their own domains. When in Edo, they were required to leave their families behind as hostages, ensuring their loyalty to the Shogun. This system not only kept the daimyos under close surveillance but also drained their resources, as maintaining residences in both Edo and their home domains was costly.

The Role of the Edo Castle

The Edo Castle served as the political and administrative center of the Tokugawa Shogunate. It was the residence of the Shogun and the hub of governmental activities. The castle’s strategic location and formidable defenses symbolized the Shogun’s power and authority.

The Role of Laws and Policies

The Tokugawa Shogunate implemented a comprehensive legal code to maintain order and control. Laws were codified to regulate the behavior of all classes, ensuring that everyone adhered to their prescribed roles within society. Punishments for transgressions were often severe, reflecting the Shogunate’s commitment to maintaining strict social order.

The political structure of the Tokugawa Shogunate was characterized by a centralized feudal system that balanced the power between the central authority of the Shogun and the autonomy of the regional daimyos. Through mechanisms like the Sankin-kotai system and a rigid social hierarchy, the Tokugawa Shogunate maintained control over Japan for more than two and a half centuries.

Social Hierarchy and Class Structure

The Tokugawa Shogunate established a rigid social hierarchy that played a crucial role in maintaining order and stability throughout Japan. This system clearly defined the roles and responsibilities of each class, ensuring that everyone adhered to their designated place in society. The social structure was divided into four main classes: samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants, with outcasts and other marginalized groups existing outside this framework.

The Four-Tier Social Hierarchy

Samurai

At the top of the social hierarchy were the samurai, the warrior class who served as the administrators and enforcers of the Shogunate’s policies. Samurai were bound by the bushido code, which emphasized loyalty, honor, and martial skill. They were the only class allowed to carry swords, a symbol of their status and authority. The samurai’s primary responsibilities included maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and serving their daimyo in both administrative and military capacities.

- Duties and Responsibilities: Enforcing laws, collecting taxes, military service.

- Privileges: Right to carry swords, receive stipends from their lords, social prestige.

Farmers

The second tier of the hierarchy consisted of farmers, who were regarded as the backbone of the Tokugawa economy. Farmers were valued for their role in producing the essential food supply that sustained the nation. Although they were considered the most important class after the samurai, their lives were often harsh and strictly regulated. Farmers were required to pay a significant portion of their harvest as taxes, which contributed to the Shogunate’s wealth and stability.

- Duties and Responsibilities: Cultivating crops, paying taxes in the form of rice or other produce.

- Privileges: Relative respect compared to other commoners, essential role in society.

Artisans

Below the farmers were the artisans, skilled craftsmen who produced tools, clothing, and other goods necessary for daily life. Artisans included blacksmiths, carpenters, weavers, and potters. While they did not enjoy the same level of respect as farmers, their work was essential to the functioning of society, and they could achieve considerable skill and recognition within their trades.

- Duties and Responsibilities: Producing goods and tools, contributing to local economies.

- Privileges: Ability to gain recognition and patronage through craftsmanship.

Merchants

At the bottom of the official social hierarchy were the merchants. Despite their low social status, merchants played a vital role in the economy by facilitating trade and distributing goods. Over time, many merchants amassed significant wealth, often surpassing that of the samurai. However, their wealth did not translate into social prestige, as their work was seen as less honorable compared to the production of goods and food.

- Duties and Responsibilities: Facilitating trade, distributing goods, managing financial transactions.

- Privileges: Potential to accumulate significant wealth, influence over local economies.

Outcasts and Marginalized Groups

Eta and Hinin

Outside the formal social hierarchy were the eta and hinin, groups subjected to significant social discrimination and marginalization.

- Eta: Engaged in tasks considered impure or tainted, such as leatherwork, butchery, and execution. The eta were often isolated in separate communities and faced severe social stigma.

- Hinin: Included beggars, itinerant performers, and other individuals deemed outside the accepted social order. Like the eta, the hinin were marginalized and subject to strict regulations.

The Place of Women in Tokugawa Society

Women in Tokugawa Japan were expected to adhere to strict societal roles based on their class. Samurai women were primarily responsible for managing the household and supporting their husbands’ duties. Women in farming communities worked alongside men in the fields and managed domestic affairs. Artisans’ and merchants’ wives often assisted in their husbands’ businesses.

- Roles and Responsibilities: Household management, supporting family businesses, agricultural work.

- Social Expectations: Obedience to male family members, maintaining family honor.

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s social hierarchy was a carefully constructed system designed to maintain order and stability. Each class had clearly defined roles and responsibilities, contributing to the overall functioning of society. While this rigid structure ensured stability, it also reinforced social inequalities and limited social mobility. Understanding this hierarchy provides valuable insights into the social dynamics and cultural values of Tokugawa Japan.

Economic Policies and Developments

The economic policies and developments during the Tokugawa Shogunate played a crucial role in shaping Japan’s economic landscape. Despite its isolationist stance, the Tokugawa Shogunate fostered economic growth, improved infrastructure, and promoted agricultural productivity, which collectively contributed to a relatively stable and prosperous society.

Agrarian Economy and Land Management

Importance of Agriculture

Agriculture was the backbone of the Tokugawa economy. The majority of the population were farmers, and rice was the primary staple and currency of the economy. The Shogunate’s policies were geared towards maximizing agricultural productivity to ensure a stable food supply and revenue base.

Land Distribution and Taxation

The Shogunate implemented a system of land distribution that ensured control over the country’s agricultural output. Daimyos were responsible for managing their domains and collecting taxes from farmers. Taxes were often paid in the form of rice, which was then used to support the samurai class and the central government. The Shogunate conducted periodic surveys (kenchi) to assess and redistribute land to maintain a balance of power and productivity.

Irrigation and Agricultural Techniques

The Tokugawa period saw significant improvements in agricultural techniques and infrastructure. The development of irrigation systems, better tools, and crop rotation methods increased agricultural yields. These advancements contributed to the overall stability and growth of the economy.

Development of Urban Centers

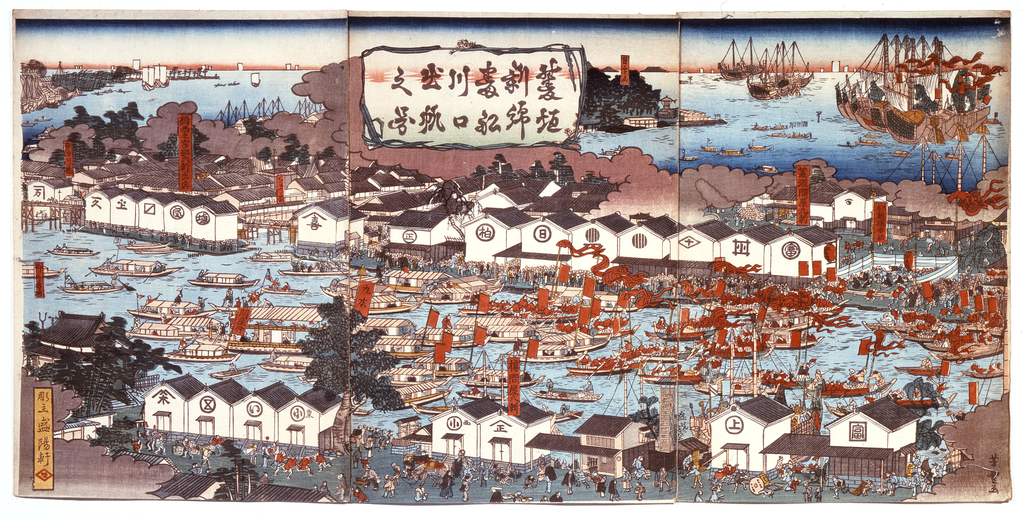

Rise of Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto

Under the Tokugawa Shogunate, urban centers flourished. Edo (modern-day Tokyo) became the political and economic hub, attracting a large population and fostering the growth of various industries. Osaka emerged as a major commercial center due to its strategic location and role as a hub for rice trade. Kyoto, the traditional capital, remained an important cultural and economic center.

Urbanization and Economic Diversification

The growth of these urban centers led to increased urbanization and economic diversification. The rise of a merchant class and the development of markets, shops, and entertainment districts contributed to the dynamic urban economy. Craftsmen, artisans, and traders thrived, catering to the needs of the growing urban population.

Trade Policies: Sakoku (Closed Country Policy)

Isolationist Policy

One of the defining features of the Tokugawa Shogunate’s economic policy was sakoku, the policy of national seclusion implemented in the 1630s. This policy restricted foreign trade and interaction, allowing only limited and controlled contact with China, Korea, and the Dutch through the port of Nagasaki.

Impact on Domestic Economy

The sakoku policy had both positive and negative impacts on the domestic economy. On one hand, it protected Japan from foreign influence and potential colonization. On the other hand, it limited access to foreign goods and technology, which could have further stimulated economic growth. Nevertheless, the policy fostered a self-sufficient economy and encouraged the development of domestic industries.

Internal Trade and Merchant Class Growth

Expansion of Internal Trade

Despite the restrictions on foreign trade, internal trade flourished during the Tokugawa period. The development of a comprehensive road network, including the Tokaido, facilitated the movement of goods and people across the country. Markets and trade fairs became common, allowing for the exchange of goods between different regions.

Rise of the Merchant Class

The growth of internal trade led to the rise of a wealthy and influential merchant class. Merchants, initially regarded as the lowest social class, played a crucial role in the economy by managing trade, finance, and distribution of goods. Many merchants accumulated significant wealth and established powerful business conglomerates, known as zaibatsu.

Currency and Monetary Policies

Introduction of a Unified Currency

To support economic activities, the Tokugawa Shogunate introduced a unified currency system. Gold, silver, and copper coins were minted and circulated, facilitating trade and commerce. The use of paper money also began to emerge, particularly in urban centers.

Financial Institutions and Credit Systems

The development of financial institutions and credit systems further supported economic growth. Moneylenders and pawnbrokers provided credit to merchants and artisans, enabling them to expand their businesses. The emergence of proto-banking institutions laid the groundwork for Japan’s modern financial system.

The economic policies and developments during the Tokugawa Shogunate significantly contributed to Japan’s stability and prosperity. The emphasis on agriculture, development of urban centers, and growth of internal trade created a robust economic foundation. While the sakoku policy limited foreign trade, it also fostered a self-sufficient economy that thrived on domestic production and innovation. Understanding these economic dynamics provides valuable insights into the success and longevity of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Cultural Flourishing Under the Tokugawa Shogunate

The Tokugawa Shogunate, despite its rigid social structure and isolationist policies, was a period of significant cultural growth and development in Japan. This era saw the flourishing of arts, literature, theater, and various cultural practices, profoundly influencing Japanese identity and heritage.

Influence of Neo-Confucianism

Intellectual and Philosophical Foundations

Neo-Confucianism became the dominant philosophical and ethical system during the Tokugawa period. Introduced from China, it emphasized a hierarchical social order, duty, and filial piety, which resonated with the Shogunate’s emphasis on social stability and order. Neo-Confucianism influenced education, governance, and societal norms, shaping the moral and ethical conduct of the populace.

Impact on Education and Bureaucracy

The spread of Neo-Confucianism led to the establishment of schools and academies, promoting literacy and learning among the samurai class. The Shogunate supported the establishment of han schools in each domain to educate samurai children, fostering a well-educated bureaucratic class capable of managing administrative duties effectively.

Development of Arts and Culture

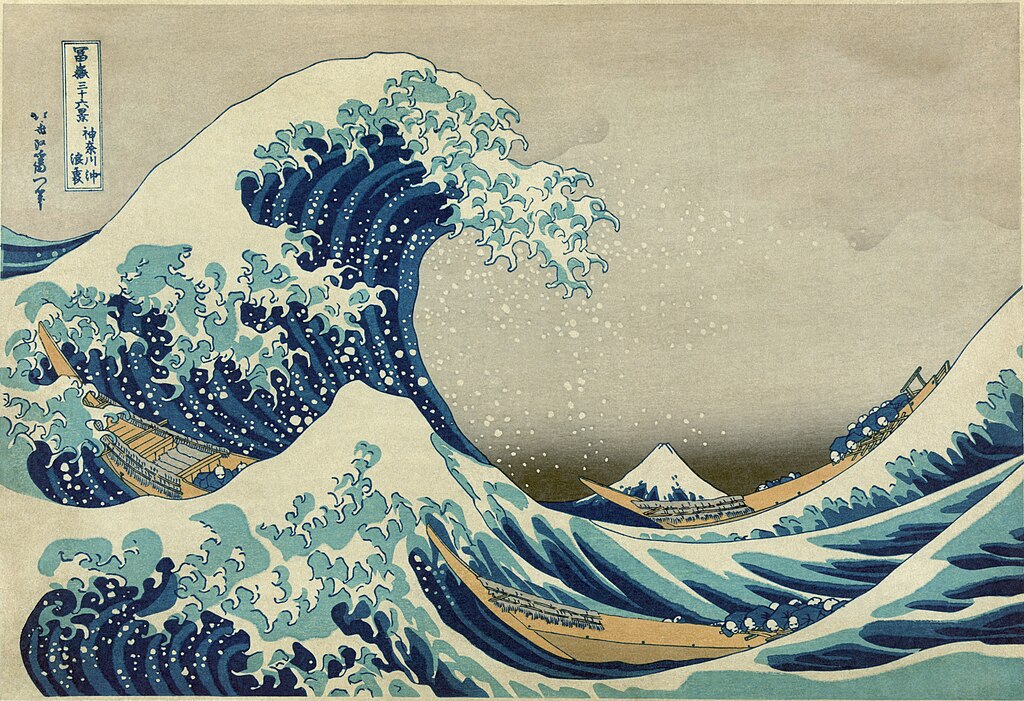

Ukiyo-e (Woodblock Prints)

The Tokugawa period saw the rise of ukiyo-e, or woodblock prints, which depicted scenes from everyday life, landscapes, and portraits of kabuki actors and courtesans. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige gained fame for their intricate and beautiful prints, which remain iconic representations of Japanese art today. Ukiyo-e prints were affordable and widely distributed, making art accessible to a broad audience.

Kabuki and Noh Theater

Theater thrived during the Tokugawa era, with kabuki and noh becoming popular forms of entertainment. Kabuki, known for its dramatic performances, elaborate costumes, and dynamic acting, appealed to the common people and often depicted stories of love, betrayal, and historical events. Noh theater, more refined and traditional, was patronized by the samurai class and featured masked performances that conveyed deep spiritual and philosophical themes.

Tea Ceremony and Ikebana

The tea ceremony (chanoyu) and the art of flower arranging (ikebana) were refined during the Tokugawa period. The tea ceremony, with its emphasis on simplicity, mindfulness, and the aesthetic appreciation of the moment, became an essential cultural practice among the samurai and merchant classes. Ikebana, the disciplined art of arranging flowers, evolved into a highly respected art form, reflecting the principles of harmony, balance, and beauty.

Educational Reforms and Literacy Rates

Han Schools and Terakoya

The Tokugawa Shogunate placed a strong emphasis on education, particularly for the samurai class. Han schools were established in each domain to educate samurai children in Confucian classics, martial arts, and administration. For commoners, terakoya (temple schools) provided basic education in reading, writing, and arithmetic. These schools contributed to a relatively high literacy rate compared to other countries at the time.

Spread of Knowledge and Learning

The spread of education and the increasing availability of printed materials led to the growth of a literate and informed populace. Books, including novels, poetry, and instructional manuals, became widely available, fostering a culture of reading and learning. The rise of commercial publishing also played a significant role in the dissemination of knowledge.

Influence of Buddhism and Shintoism

Syncretism and Religious Practices

Buddhism and Shintoism coexisted and often blended during the Tokugawa period, creating a unique religious syncretism. Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines were central to community life, serving as places of worship, social gatherings, and education.

Pilgrimages and Festivals

Religious pilgrimages and festivals were integral parts of Tokugawa culture. Pilgrimages to famous shrines and temples, such as Ise Shrine and Mount Koya, were popular among all classes, fostering a sense of spiritual connection and national identity. Festivals, celebrating seasonal changes and local deities, were important communal events that reinforced cultural traditions and social bonds.

The Tokugawa Shogunate was a period of remarkable cultural flourishing, marked by the development and refinement of various art forms, educational advancements, and religious practices. The influence of Neo-Confucianism, the rise of ukiyo-e and theater, and the emphasis on education and literacy contributed to a vibrant and dynamic cultural landscape. This era laid the foundations for many aspects of modern Japanese culture, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to be celebrated and appreciated today.